|

- Books by Frank Frazetta The Fantastic Art of Frank Frazetta Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Icon Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Frank Frazetta, Book 2 Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Legacy: Selected Paintings and Drawings by the Grand Master of Fantastic Art, Frank Frazetta Frank Frazetta $27.59 - $84.09  Frank Frazetta - Book Four Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Frazetta: Illustrations Arcanum (Illustrators Artbook Series) Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Frank Frazetta: Rough Work (Spectrum Presents) Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Frank Frazetta, Book 3 Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  RGK: The Art of Roy G. Krenkel Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Frank Frazetta's Adventures of the Snow Man Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Frank Frazetta: Master Of Fantasy Art Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Frank Frazetta - Book Five Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Frazetta Sketchbook (Vol I) Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Golden Treasury of Krazy Kool Klassic Kids' Komics Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  The Sensuous Frazetta Frank Frazetta $33.43  Al Capp's Li'l Abner: The Frazetta Years Volume 4 (1960-1961) Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Classic Comics Illustrators: The Comics Journal Library (Burne Hogarth, Frank Frazetta, Mark Schultz, Russ Heath and Russ Manning) Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Al Capp's Li'l Abner: The Frazetta Sundays, Vol. 2: 1956-57 Frank Frazetta $19.59  Frank Frazetta's Death Dealer Deluxe HC Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Frazetta Funny Stuff Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Thun'da, King Of The Congo Archive Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Frazetta Pillow Book Frank Frazetta $30.09  Johnny Comet Frank Frazetta $9.59  Haunted Horror Pre-Code Cover Coloring Book, Volume 1 Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  witzend Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  The Complete Frazetta Johnny Comet Frank Frazetta $21.85  Frazetta Johnny Comet Deluxe Frank Frazetta Out of Stock  Small Wonders: The Funny Animal Art of Frank Frazetta Frank Frazetta $12.29  White Indian Frank Frazetta $21.80  Cripta Volume 4 Frank Frazetta Out of Stock More by Frank Frazetta Bibliography of Frank Frazetta-

Frank Frazetta (February 9, 1928 - May 10, 2010)

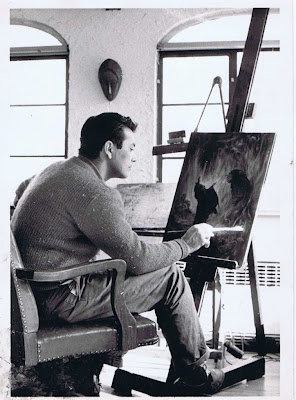

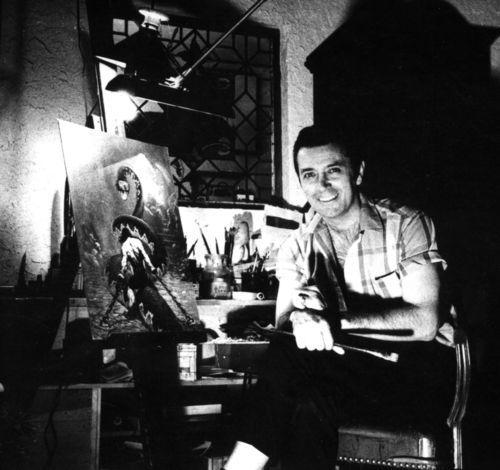

Frazetta was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. At the age of eight, at the insistence of his school teachers, Frazetta's parents enrolled him in the Brooklyn Academy of Fine Arts. He attended the academy for eight years under the tutelage of Michele Falanga, an award-winning Italian fine artist. Falanga was struck by Frazetta's significant talent. Frazetta's abilities flourished under Falanga, who dreamed of sending Frazetta to Europe, at his own expense, to further his studies. Unfortunately, Falanga died suddenly in 1944 and with him, his dream. As the school closed about a year after Falanga's passing, Frazetta was forced to find work to earn a living. At 16, Frazetta started drawing for comic books that varied in themes: westerns, fantasy, mysteries, histories and other contemporary themes. Some of his earliest work was in funny animal comics, which he signed as "Fritz". During this period he turned down job offers from comic giants such as Walt Disney. In the early 1950s, he worked for EC Comics, National Comics (including the superhero feature "Shining Knight"), Avon and several other comic book companies. Much of his work in comic books was done in collaboration with friends Al Williamson and Roy Krenkel.

Through the work on the Buck Rogers covers for Famous Funnies, Frazetta started working with Al Capp on his Li'l Abner comic strip. Frazetta was also producing his own strip, Johnny Comet at this time, as well as assisting Dan Barry on the Flash Gordon daily strip. In 1961, after nine years with Capp, Frazetta returned to regular comics. Having emulated Capp's style for so long, Frazetta's own work during this period looked a bit awkward as his own style struggled to reemerge. Work in comics for Frazetta was hard to find, however. Comics had changed during his period with Capp and his style was deemed antiquated. Eventually he joined Harvey Kurtzman doing the parody strip Little Annie Fanny in Playboy magazine.

By 1964, one of Frazetta's magazine ads caught the eye of United Artists studios. He was approached to do the movie poster for What's New Pussycat and earned his yearly salary in one afternoon. He did several other movie posters (see notable works). Frazetta also started producing paintings for paperback editions of adventure books. His cover for the sword-and-sorcery collection Conan the Adventurer by Robert E. Howard and L. Sprague de Camp (Lancer 1966) caused a sensation-numerous people bought the book for its cover alone. From this point on, Frazetta's work was in great demand. During this period he also did covers for other paperback editions of classic Edgar Rice Burroughs books, such as those from the Tarzan and Barsoom (John Carter of Mars) series. He also did several pen and ink illustrations for many of these books.

Since this time, most of Frazetta's work has been commercial in nature, providing paintings and illustrations from things such as movie posters to book jackets to calendars. Many of his paintings are uncommissioned but have nonetheless become highly sought after commercially.

Frazetta's work has long been admired by many Hollywood personalities. Clint Eastwood and George Lucas-fans and friends of Frazetta's-have commissioned works from him for some of their movie projects.

Once he secured a reputation, movie studios started trying to lure him to work on animated movies. Most, however, would give him participation in name only-most of the creative control would be held by others. Finally in the early 1980s a movie deal was offered which would give him most creative control. Frazetta worked with animated movie producer Ralph Bakshi on the feature Fire and Ice released in 1983.

Many of the characters and most of the story were Frazetta's creations. The movie proved to be a commercial disappointment, however, as Frazetta's fantastic imagery could not be sufficiently reproduced via then-current animation technology and methods. Frazetta soon returned to his roots in painting and pen and ink illustrations.

Today, Frazetta's work is so highly regarded that even incomplete sketches of his sell for thousands of dollars. Frazetta's primary commercial works are in oil, but he also works with watercolor, ink and pencil alone. In his later life, Frazetta has been plagued by a variety of health problems, including a thyroid condition that went untreated for many years. Recently, a series of strokes has impaired Frazetta's manual dexterity to a degree that he has switched to drawing and painting with his left hand. He still continues to find an outlet through sculpture and other means.

The cover of Wolfmother's debut album features Frazetta's "The Sea Witch"Frazetta's paintings have been used by a number of recording artists as cover art for their albums. Molly Hatchet's first 2 albums feature "The Death Dealer" and "Dark Kingdom" respectively. Dust's second album, Hard Attack, features "Snow Giants". Nazareth used "The Brain" for their 1977 album Expect No Mercy. Recently, Wolfmother used "The Sea Witch" as the cover for their self-titled debut. Wolfmother has also used other Frazetta paintings for the covers of their singles.

In 2003, a feature film documenting the life and career of Frazetta was released entitled, Frazetta: Painting With Fire. Mr. Frazetta died of a stroke on May 10, 2010, in a hospital near his residence in Florida.

0 Comments

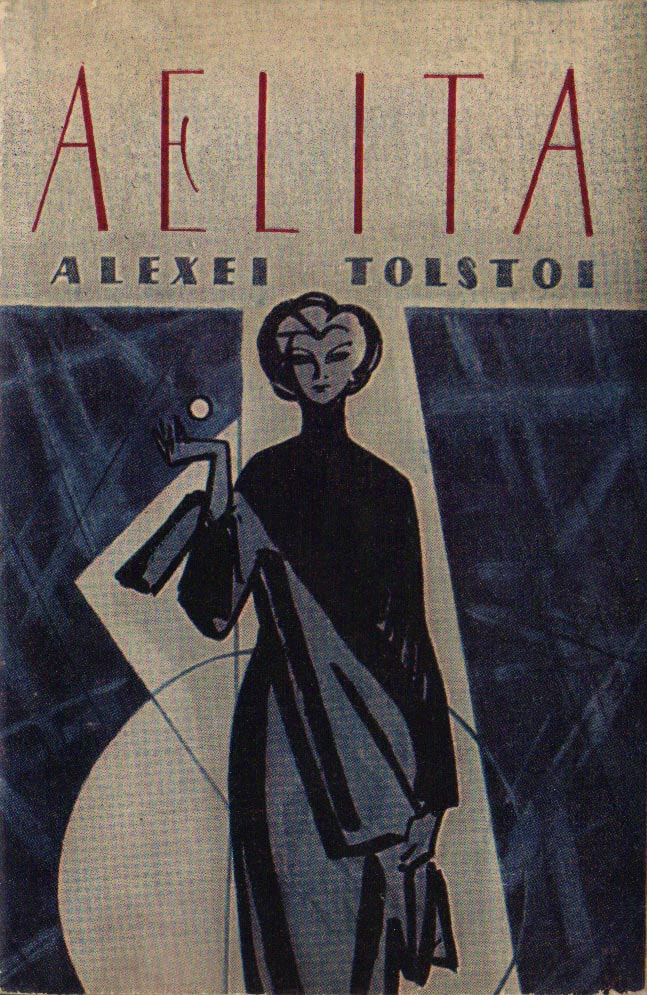

7/11/2021 0 Comments Aelita princess of mars

1 LIBRARY OF SOVIET LITERATURE

A E L I T A

by

Alexei Tolstoi

TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN BY LUCY FLAXMAN

FOREIGN LANGUAGES PUBLISHING HOUSE Moscow

2 TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN BY LUCY FLAXMAN

EDITED BY V. SHNEERSON

DESIGNED BY A. VASIN

Printed in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics CONTENTS

A Strange Notice The Workshop

The Descent Mars The Deserted House The Sunset Los Looks at the Earth The Martians Beyond the Mountains Soatsera In the Azure Copse Rest The Ball of Mist On the Stairs Aelita's First Story A Chance Discovery Aelita's Morning Aelita's Second Story

Gusev Observes the City Los Is Alone The Spell The Song of Long Ago Los Flies to Gusev's Aid Gusev's Activities Events Take a New Turn The Counter-Attack Queen Magr's Labyrinth Khao Escape Oblivion The Earth

The Voice of Love

4 A STRANGE NOTICE

A strange notice appeared in Krasniye Zori Street. It was written on a small sheet of grey paper, and nailed to the peeling wall of a deserted building. Walking past the house, Archibald Skiles, the American newspaper correspondent, saw a barefoot young woman in a neat cotton-print frock standing before the notice and reading it with her lips. Her tired, sweet face showed no surprise; her blue eyes, with a little fleck of madness in them, were unmoved. She tucked a lock of wavy hair behind her ear, lifted her basket of vegetables and crossed the street.

As it happened, the notice merited greater attention. His curiosity aroused, Skiles read it, moved closer, rubbed his eyes, and read it again.

"Twenty-three," he muttered at last, which was his way of saying, "I'll be damned!" The notice read as follows:

"Engineer M. S. Los invites all who wish to fly with him to the planet of Mars on August 18, to call on him between 6 and 8 p.m. at 11, Zhdanovskayia Embankment." It was written as simply as that, in indelible pencil. Skiles felt his pulse. It was normal. He glanced at his watch. The time was ten past four of August 17, 192. . . .

Skiles had been prepared for anything in that crazy city, but not for this, not the notice on the peeling wall. It unnerved him.

The wind swept down the empty street. The big houses with their broken and boarded windows, seemed untenanted. Not a single head showed in them. The young woman across the street put down her basket and stared at Skiles. Her sweet face was calm but weary.

Skiles bit his lip. He pulled out an old envelope and jotted down Los's address. While he was thus engaged, a tall, broad-shouldered man, a soldier, to judge by his clothes—a beltless tunic and puttees—stopped by the notice. He had no cap on,

5 and his hands were thrust idly into his pockets. The back of his strong neck tensed as he read.

"Here's a man—taking a swing at Mars!" he muttered with unconcealed admiration, turning his tanned, cheerful face to Skiles. There was a scar across his temple. His eyes were a grey-brown, with little flecks in them, like those of the barefoot woman. (Skiles had long since noted these curious flecks in Russian eyes, had even mentioned the fact in one of his articles, to wit: "... the absence of stability in their eyes, now mocking, now fanatically resolute, and lastly, that baffling expression of superiority—is highly painful to the European.")

"I've a good mind to fly with him—as simple as that," he said, looking Skiles up and down with a good-natured smile.

Then he narrowed his eyes. His smile vanished. He had noticed the woman standing across the street beside her basket. Jerking up his chin, he called to her:

"What are you doing there, Masha?" (She blinked her eyes rapidly.) "Get along home." (She shifted her small dusty feet, sighed, hung her head.) "Get along, I say, I'll be home soon." The woman picked up her basket and walked away. "I've been demobbed, you know—shell-shocked and wounded. Spend my time reading notices—bored stiff," the soldier said. "Are you going to see this man?" Skiles inquired. "Certainly."

"But it's preposterous—flying fifty million kilometres through space...." "Yes. It is pretty far." "The man's a fraud—or a raving lunatic." "You never can tell." It was Skiles who narrowed his eyes now as he studied the soldier. There it was, that mocking expression, that baffling look of superiority. He flushed with anger and stalked off in the direction of the Neva River. He strode along confidently, with long swinging steps. In the park he sat on a bench, shoved his hand into his pocket where, like the inveterate smoker and man

6 of business that he was, he kept his tobacco shreds, filled his pipe with a jab of his thumb, lit up, and stretched out his legs.

The full-grown lime-trees sighed overhead. The air was warm and damp. A little boy, naked except for a dirty polka-dot shirt, was sitting on a sand-pile. He looked as though he had been there for hours. The wind ruffled his soft flaxen hair. He was holding a string to which the leg of an ancient, draggle-tailed crow was tied. The crow looked sullen and cross, and, like the boy, glared at Skiles.

Suddenly—for the fraction of \a second—he felt dizzy. His head whirled. Was he dreaming? Was all this—the boy, the crow, the empty houses, deserted streets, strange glances, and that little notice inviting him to Mars—was it alt a dream?

Skiles took a long draw at his strong tobacco, unfolded his map of Petrograd and traced the way to Zhdanovskaya Embankment with the stem of his pipe.

THE WORKSHOP

Skiles walked into a yard littered with rusty iron scrap and empty cement I barrels. Sickly blades of grass grew on the piles of rubbish, between tangled coils of wire and broken machine parts. The dusty windows of a tall shed at the far end of the yard reflected the setting sun. In its low doorway a worker sat mixing red lead in a bucket. Sidles asked for Engineer Los. The man jerked his head towards the shed. Skiles entered.

The shed was dimly lit. An electric bulb covered with a tin cone hung over a table piled with technical drawings and books. A tangle of scaffolding rose ceiling-high at the back of the shed. There was a blazing forge, fanned by another worker. Skiles saw the studded metal surface of a spheric body gleaming through the scaffolding. The crimson rays of the

7 setting sun and the dark clouds rising from the sea were framed in the open gate outside. "Someone here to see you," said the worker at the forge.

A broad-shouldered man of medium height emerged from behind the scaffolding. His thick crop of hair was white, his face young and clean-shaven, with a large handsome mouth and piercing, light-grey, unblinking eyes. He wore a soiled homespun shirt open at the throat, and patched trousers held up by a piece of twine. There was a stained drawing in his hand. As he approached Skiles he fumbled at his throat in a vain attempt to button his shirt.

"Is it about the notice? D'you want to fly?" he asked in a husky voice. He offered Skiles a chair under the electric bulb, sat down facing him, laid his drawing on thu table, and filled his pipe. It was Engineer Mstislav Sergeyevich Los.

Lowering his eyes, he struck a match. Its flame Illumined his keen face, the two bitter lines near his mouth, the broad sweep of his nostrils and his long dark eyelashes. Skiles liked that face. He said he had no intention of flying to Mars but that he had read the notice in Krasniye Zori Street, and deemed it his duty to inform his readers of so extraordinary and sensational a project as Los's interplanetary trip.

Los heard him out, his unblinking eyes fixed on his face. "Pity you won't fly with me. A great pity!" He shook his

head. "People shy away from me the moment I mention the subject. I expect to take off in four days and haven't found a companion yet." He struck another match, and blew out a cloud of smoke. "What d'you want to know?" "The story of your life."

"It can be of no interest to anybody," said Los. "There's nothing remarkable about it. I went to school on a pittance and shifted for myself since I was twelve. My youth, my studies, and my work—there's nothing in them to interest your readers, nothing—except ..." Los frowned and set his mouth, "this contraption." He jabbed his pipe at the scaffolding. "I've been

8 working on it a long time. Started building two years ago. That's all."

"How many months d'you expect it to take you to reach Mars?" Skiles asked, studying the point of his pencil.

"Nine or ten hours, I think. Not more." "Oh!" Skiles reddened. His mouth twitched.

"I would be very much obliged," he began with studied politeness, "if you were to trust me more, and treat our interview seriously."

Los put his elbows on the table and enveloped himself in a cloud of smoke. His eyes gleamed through the haze.

"On August 18, Mars will be forty million kilometres away from the Earth. This is the distance I shall have to fly. First, I shall have to get through the layer of the Earth's atmosphere, which is 75 kilometres. Second, the space between the planets, which is 40 million kilometres. Third, the layer of the Martian atmosphere—65 kilometres. It is only those 140 kilometres of atmosphere that matter."

He rose and dug his hands into his trouser pockets. His head was in the shadow. All Skiles saw was his exposed chest and hairy arms with the rolled up shirtsleeves.

"Flight is usually associated with a bird, a falling leaf, or a plane. But these do not really fly. They float. In the strict sense of the word, flight is the drop of a body propelled by the force of gravity. Take a rocket. In space, where there is no resistance, where there is nothing to obstruct its flight, a rocket travels with increasing velocity. I am likely to approach the velocity of light if no magnetic influences interfere. My machine is built on the rocket principle. I shall have to pierce 140 kilometres of terrestrian and Martian atmosphere. This will take an hour and a half, including the take-off and landing. Add another hour for climbing out of the Earth's gravitational field. Once I am in space, I shall be able to fly at any speed I like. There are just two dangers. One is that my blood vessels might burst from excessive acceleration, and the other, that the machine might hit the Martian atmosphere at too great a speed. It would be like

9 striking sand. The machine and everything in it would turn into gas. Particles of planets, of unborn or perished worlds, hurtle through interstellar space. Whenever they enter the atmosphere they burn up. Air is an almost impenetrable shield, although apparently it was pierced at one time on our planet."

Los pulled his hand out of his pocket, laid it on the table under the light and clenched his fist.

"In Siberia, amid the eternal ice, I dug up mammoths that had perished in the cracks of the earth. I found grass in their teeth— they had once grazed in regions now bound by ice. I ate their meat. They had not decomposed, frozen as they were and buried in snow. The Earth's axis had apparently deflected very abruptly. The Earth either collided with some celestial body, or we had a second satellite revolving round us, smaller than the moon. The Earth must have attracted it, and it collided with the Earth and shifted its axis. It could very well have been this impact that destroyed the continent in the Atlantic Ocean lying west of Africa. To avoid disintegrating when I rocket into the Martian atmosphere, I shall have to keep down my speed. This is why I allow six or seven hours for the flight in outer space. In a few years travelling to Mars will be as simple as flying, say, from Moscow to New York."

Los stepped away from the table and threw an electric switch. Arc lights went on, hissing overhead under the ceiling. Skiles saw drawings, diagrams and maps pinned on the board walls, shelves loaded with optical and measuring instruments, space-suits, stacks of tinned food, fur clothes and a telescope on a dais in the corner.

Los and Skiles walked over to the scaffolding built round the metal egg. Skiles estimated that it was roughly 8 1/2 metres high and 6 metres in diameter. A flat steel belt ran round its middle, projecting over its lower part like an umbrella. This was the parachute brake to increase the machine's resistance during its drop through the atmosphere. There were three portholes under the parachute. The bottom of this egg-like machine terminated in a narrow neck girdled by a double spiral

10 of massive steel—the buffer to absorb the shock during the landing.

Tapping his pencil on the riveted shell, Los embarked on a detailed description of his interplanetary ship. It was built of pliable refractory steel, fortified from within with ribs - and lightweight framework. So much for the outer casing. Inside it was a second casing made of six layers of rubber, felt and leather, which contained observation instruments and various appliances, such as oxygen tanks, carbonic acid absorbers, and shock-absorbent containers for instruments and provisions. Special "peepholes" made of short metal tubes and prismatic glasses projected beyond the outer casing.

The propulsion mechanism was installed in the spiral-choked neck made of a steel harder than astronomical bronze. Vertical canals were drilled in it, each of which broadened at the top to issue into a detonation chamber. The chambers were equipped with spark plugs and feeders. Just as gasoline is fed to a motor, ultralyddite, a fine powder of unusual explosive force, was fed to the detonation chambers. Discovered by a Petrograd factory, ultralyddite was more powerful than any other known explosive. The jet produced by the explosive was cone-shaped and had an exceedingly narrow base. To ensure that the axis of the jet coincided with the axis of the vertical canals of the neck, the ultralyddite fed to the detonation chambers was first passed through a magnetic field.

This was the general principle of the propulsion mechanism. It was a rocket. Its supply of ultralyddite would last for 100 hours. The velocity of the machine was regulated by decreasing or increasing the number of detonations per second. Its lower part was much heavier than the upper, which would cause it to turn neck foremost towards the field of gravitation. "Who financed your project?" asked Skiles. Los looked surprised.

"Why, the Republic...."

11 The two went back to the table. After a moment's silence, Skiles asked somewhat uncertainly: "D'you think you'll find any living beings on Mars?"

"I'll have an answer to that on Friday morning, August 19." "I offer you ten dollars per line of your travel notes. You can have the money in advance for six articles of 200 lines each, the check to be cashed in Stockholm. How about it?" Los laughed and nodded. Skiles perched on a corner of the table to write out the check.

"Pity you won't come with me. It's really a short trip. Shorter, in fact, than hiking from here to Stockholm," said Los, puffing on his pipe.

12 A FELLOW-TRAVELLER

Los stood leaning against the gatepost. His pipe was cold. Beyond the gate, an empty lot stretched all the way to the bank of the Zhdanovka. On the other side of the river loomed the blurred outlines of trees on Petrovsky Island, tinged by the melancholy sunset. Wisps of clouds, touched by the sun's glow, were scattered like islands in the expanse of greenish sky, studded with a few twinkling stars. All was quiet on old Mother Earth.

Kuzmin, the worker who had been mixing red lead, strolled up to the gate. He flicked his burning cigarette into the darkness.

"It isn't easy, parting with the Earth," he said softly. "It's hard enough leaving home. You keep looking back as you pack off to the railway station. My house may have a thatch roof, but it's mine, and there's no place like home. As for leaving the Earth—"

"The kettle's boiling," said Khokhlov, the other worker. "Come, Kuzmin, and have your tea."

Kuzmin sighed. "Yes, that's that," he said, retracing his steps to the forge. Sullen Khokhlov and Kuzmin sat on a couple of crates. They carefully broke their bread, picked the bones out of the sun-cured fish and chewed it unhurriedly. Jerking his beard, Kuzmin said in an undertone:

"I'm sorry for the old man. There aren't many like him in the world." "He isn't dead yet, is he?"

"A flyer told me he climbed close to eight versts—it was summer, mind you—and his oil froze. Can you imagine what it is like higher up? Must be ice-cold, and pitch dark."

"What I say is, he isn't dead yet," Khokhlov repeated sullenly.

13 "There isn't a soul who wants to fly with him. Nobody believes him. The notice has been up on the wall for over a week." "I believe him." "You think he'll get there?"

"He will. And they'll sit up and take notice in Europe then." "Who'll sit up?"

"They'll sit up, I'm telling you. And they'll have to like it or lump it. Who'll Mars belong to, eh?—the Soviets." "Why, that'd be great!"

Kuzmin made room on his crate for Los. The engineer sat down and took up a tin mug of steaming tea. "Won't you fly with me, Khokhlov?" "No," Khokhlov said. "I'm scared." Los smiled, took a sip of his tea and turned to Kuzmin. "What about you, my friend?"

"I'd be glad to, but my wife is a sick woman, and then there are the children. Cant very well leave them, can I?"

"Yes, it seems I'll have to fly alone," said Los, setting down the empty mug and wiping his lips with his hand. "Volunteers are scarce." He smiled again and shook his head. "A girl came to see me about it yesterday. I’ll come with you,' she said. Tm nineteen; I can sing, dance and play the guitar, and I want to leave the Earth—I'm sick of all these revolutions. Will I need an exit visa?' After our little talk she sat down and cried. 'You cheated me,' she wailed, 'I thought it was much nearer.' Then there was a young man. He spoke in a deep bass voice and had moist hands. 'D'you take me for an idiot?' he boomed. 'You can't fly to Mars. How dare you hang up such notices?' It was all I could do to pacify him."

Los rested his elbows on his knees and gazed at the coals. His face looked tired and drawn. He seemed to be relaxing after a long strain. Kuzmin went to get some tobacco. Khokhlov coughed. "Aren't you scared at all?"

Los turned on him his eyes warmed by the flaming coals.

14 "No, I'm not. I'm sure I'll make it. And if I don't, the end will be too swift to be painful. There's something else that worries me. Suppose I miscalculate and miss the Martian field of gravitation. My supplies of fuel, oxygen and food will last for a long time. And there I'll be flying in the dark, with a star shining somewhere ahead. A thousand years from now my frozen corpse will plunge into its fiery oceans. Just think of my corpse flying through obscurity for a thousand years! And the long days of anguish when I'll still breathe—I'll live for days and days in that box, all alone in the universe! It isn't dying that scares me, but the solitude, the hopeless solitude in eternal obscurity. That's the thing I'm afraid of. I'd hate to fly by myself."

Los stared at the coals with narrowed eyes, his mouth set obstinately. Kuzmin appeared in the door and called softly: "Someone to see you." "Who is it?" Los rose to his feet. "A Red Army man."

Kuzmin came in, followed by the man in the beltless tunic who had read the notice in Krasniye Zori Street. He nodded to Los, glanced at the scaffolding, and approached the table. "Need a travelling companion?" Los offered him a chair and sat down facing him. "Yes, I'm looking for someone to come with me to Mars."

"I know—I read the notice. I had a man show me the star in the sky. It's a long way. What are the terms—the pay and keep?" "Are you a family man?" "I've got a wife, but no children." He drummed on the table with his fingers and inspected the shed curiously. Los told him briefly about the flight, and warned him about the risk. He promised to provide for his wife, and said he would give him his wages in advance, in cash and provisions. The Red Army man nodded absently.

"Do you know what we'll find there? Men or monsters?"

15 Los scratched the back of his head and laughed. "There ought to be people—something like us. We'll see when we get there. It's like this—for some years now, the big radio stations in Europe and America have been receiving :strange undecipherable signals. They were first thought to be caused by magnetic storms. But they were too much like alphabetic signals. Someone is trying to contact us. Who can it be? As far as we know, there's no life on any of the planets, outside Mars. That's the only place the signals can come from. Look at its map—it's covered with a network of canals (he pointed to a drawing of Marls nailed to the wall). They seem to have a very powerful radio station. Mars is calling the Earth. So far, we have been unable to reply. But we can fly there. It is scarcely possible that the radio stations on Mars were built by monsters or creatures unlike us. Mars and the Earth are two tiny globes revolving in close proximity. The laws are the same for both of us. The dust of life flies about the universe. The same spores settle on Mars and the Earth, and all the myriad frozen stars. Life appears everywhere, and it is governed everywhere by man-like creatures. There is no animal more perfect than man."

"I'm coming with you," said the Red Army man resolutely. "When do I bring my things?" "Tomorrow. I must show you round the ship. Your name?" "Alexei Ivanovich Gusev." "Occupation?"

Gusev glanced at Los absent-mindedly, then lowered his eyes to his fingers tapping the table.

"I've been to school," he said, "I know something about motor-cars, flew a plane as an observer, fought in the war since I was eighteen. That's my story in a nutshell. I was wounded several times, and am now in the reserve." Suddenly he rubbed the crown of his head savagely and laughed. "The things I've been through in the last seven years! To tell the truth, I ought to have had the command of a regiment by now—but I'm too hot-headed. As soon as the fighting died down I'd grow restless--

16 couldn't wait till we were in the fray again. I'd go off my rocket —ask to be sent on an assignment, or simply run away." (He rubbed his head again and grinned.) "I founded four republics

— can't recall the cities now, and one time I rallied something like three hundred chaps to go and liberate India. But we got lost in the hills on the way, were caught in a storm and a landslide. Our horses were all done for. Few of us got back. Then I spent two months with Makhno—felt like going on a spree. But the bandits were a bit too thick for me—I joined the Red Army. Chased the Poles out of Kiev all the way to Warsaw with Budyonny's cavalry. Got wounded the last time, when we stormed Perekop, and was laid up for about a year. When I left hospital I didn't know what to do with myself. Then I met this girl of mine, and married her. She's a good soul. I've a soft spot for her, but I can't stay at home. And there's no point in going back to the village—my folks are all dead and the land's gone to seed. Nothing to do in town either. The war is over, and it's not likely we'll have another one soon. Take me on, Mstislav Sergeyevich. I might come in handy out there, on Mars."

"Good," said Los. He shook Gusev's hand. "See you tomorrow."

A SLEEPLESS NIGHT

Everything was ready for the takeoff. But the two men scarcely slept the next two days, stowing away countless trifles in the spaceship's containers.

They tested the instruments, tore down the scaffolding, and pulled part of the roof out in the shed.

Los introduced Gusev to the propulsion mechanism and the key instruments. His travelling companion, he saw, was both intelligent and shrewd.

17 They fixed the hour of their departure for 6 p.m. the following day.

Late at night, Los sent Gusev and the workers away. He put out all the lights but one and lay down fully dressed on the iron cot behind the telescope in the corner.

It was a quiet, starry night. Los did not sleep. He clasped his hands behind his head and stared into the dark. He had had no chance to relax for days and days. But this last night on Earth he'd let himself go: weep, man, weep and torment yourself.

Painful memories came flooding in, memories of a semi-dark room, a candle shaded by a book. The air heavy with the smell of medicine. A basin on the rug by the bed. Every time he got up and stepped past it, blurred shadows danced on the dreary wallpaper. His heart gave a twist. There, on the bed, lay Katya, the dearest thing in his life, his wife—her breath coming in quiet, short gasps. Her thick, tangled hair spread over the pillow, and her knees were raised under the quilt. Katya was leaving him. Her gentle face had changed. It was flushed and restless. She pulled out her hand from under the quilt and plucked at its edge with her fingers. Los kept taking her hand in his and tucking it under the quilt again., "Open your eyes, dear, look at me." She murmured plaintively, barely above a whisper, "Op win, op win." Her childish, barely audible, plaintive voice was trying to say, "Open the window." His feeling of pity was more terrible than fear. "Katya, Katya, look at me." He kissed her cheek, her forehead, her closed eyes. Her throat trembled, her chest rose convulsively, her fingers clutched the edge of the quilt. "Katya, Katya, what is it, my love?" No answer. She was going. ... She lifted herself on her elbows, arched her chest, as though pushed by someone, tormented. Her head fell back. She slipped down, deep into the bed. Her jaw fell. Los, shaken, took her in his arms, clung to her. No, no, no—he could not reconcile himself with Death.

Los rose from the cot, took a pack of cigarettes off the table, lit up and paced the dark shed. Then he climbed the steps

18 to the telescope dais and trained the lens on Mars high over Petrograd. He gazed long at the bright, glowing little ball. It shimmered in the lens.

He lay down again. A new vision rose in his memory— Katya sitting in the grass on a mound. Away beyond the undulating fields shone the golden domes of Zvenigorod. Kites were gliding in the summer heat over the corn and buckwheat. Katya felt lazy, it was very hot. Sitting beside her, chewing a stalk of grass, Los gazed at her fair hair, her suntanned shoulders, and the strip of white between the tan of her skin and her dress. Her grey eyes were untroubled and beautiful. There were kites gliding in them too. She was eighteen. She sat there saying nothing. Los thought to himself, "Oh no, my dear, I have more important things to do than sit here and fall in love with you. I'm not going to get hooked. I shan't come out to the country to see you again."

Lord! How stupid he had been to have let those sultry summer days go to waste. If time could only have stopped in its pace then! But it was gone, never to return!...

Los got up, struck a match, lit a cigarette and began to pace the floor again. But striding up and down by the wall like a caged beast was worse still.

He opened the door and searched the sky for Mars, which had risen to its zenith.

"It'll be just as bad up there. I shan't escape from myself even beyond the Earth's limits and outside the bounds of Death. Why did I have to poison myself with love? Much better to have lived unaroused. Aren't the frozen seeds of life, the icy crystals floating in the ether, deep in slumber? But I, I had to fall and sprout—to learn the meaning of the awful thirst of love, of merging, of losing myself, of ceasing to be a solitary seed. And all this brief dream only to re-encounter death, and separation, and to float again, a frozen crystal."

Los lingered at the gate. High over sleeping Petrograd Mars glittered, now blood-red, now blue. "A new and fascinating world," Los thought, "a world long dead, perhaps, or

19 fantastically lush and perfect. I'll stand there one night, just as I am standing here now, looking up at my native planet among the other stars. And I'll think of the mound, and the kites, and of Katya's grave. And my grief will no longer weigh me down."

In the early hours of the morning Los dug his head into his pillow and fell asleep. He was roused by the clatter of carts on the embankment. He rubbed his cheek. His eyes, sleep-laden, stared blankly at the maps on the walls and at the contours of the spaceship. He sighed, and fully awake now, went over to the wash-basin and doused his head in the icy water. Then he put on his coat and strode across the empty lot to his flat, where Katya had died six months before.

Here he washed and shaved, put on clean underwear and clothes, and checked the windows. They were fastened. The flat was not lived in. A layer of dust had settled on the furniture. He opened the door into the bedroom where he had not slept since Katya died. The shades were pulled down, and it was almost dark. Only the mirror on Katya's wardrobe door glimmered dimly. The door was half-open. Los frowned. He tiptoed over to it, closed it, then locked the bedroom door, walked out of the flat, locked the front door and put the key in his waistcoat pocket.

Now he was ready to leave.

THE SAME NIGHT

That same night Masha waited a long time for her husband. She heated the tea kettle on the primus stove over and over again, but the ominous silence outside the tall oaken door remained unbroken.

Gusev and Masha occupied a room in what was once a lavish mansion. Its owners had abandoned it during the

20 Revolution. In the four years since, the rain and the blizzards had done a good deal of damage to it.

The room was big. On the ceiling, among the gilded ornaments and clouds, floated a plump smiling woman, with winged cherubs capering about her.

"See her, Masha?" Gusev was wont to say, pointing at the ceiling, "See that jolly lass? Plump she is, and has six babies. That's what I call a woman!"

Over the gilded bed with lion's paws hung a portrait of an old tight-lipped man in a powdered wig with a star on his coat. Gusev nicknamed him "General Boots."

"He's the kind that never lets you off," he'd say. "Get on the wrong side of him, and he'll give you a taste of his boot." Masha was afraid to look at the portrait. A smoky pipe stretched across the room from a little iron stove, staining the walls with soot. The shelves and the table on Which Masha cooked their frugal meals were very tidy.

The carved oaken door opened into a hall with a double row of windows. The broken panes were boarded up, and the ceiling had cracked in places. On gusty nights, the wind roamed in it freely, and mice scuttled across the floor.

Masha sat at the table. The primus stove sputtered. From afar the wind carried the mournful chimes of a clock. It struck two. There was no sign of Gusev.

"What does he want? What more does he need?" Masha thought. "Never satisfied, my restless darling. Alyosha, Alyosha, if you'd just shut your eyes and rest your head on my shoulder, sweetheart; no need to search, you'll never find anything like the love I have for you."

Tears glistened on her eyelashes. She wiped them unhurriedly and cupped her cheek in her hand. Overhead floated the jolly woman with her frolicking cherubs. Masha thought, "If I were like her, he'd never leave me."

Gusev had told her he was going away on a long trip, but had not said where, and she had been afraid to ask. She was aware that he could not go on living with her in the queer room,

21 in that graveyard stillness, deprived of his former freedom. It was more than he could stand. He had nightmares—he would suddenly gnash his teeth, mutter, sit up, breathing hard, his face and chest dripping with sweat. Then he would go back to sleep, waking up next morning depressed and restless.

Masha was gentle with him—wiser than a mother. He loved her for it, but when morning came he would be anxious to foe gone again.

Masha had a job, and brought home food rations. They often went without a kopek. Gusev picked up various jobs, but never kept them for long. "Old folks say there's a land of gold in China," he used to remark. "There's no such land there, of course, but I've never been out that way. I'll go there, Masha, and see what it's like."

Masha dreaded the moment when Gusev would leave her worse than death itself. She had nobody else in the world. She had been a sales-girl in the shops, and a cashier on the little Neva boats ever since she was fifteen. It had been a joyless and solitary existence.

A year ago, on a holiday, she had met Gusev in a park. He had said, "I see you're all alone. Mightn't we pass the time together? I hate being alone." She had looked at him closely. He had a nice face, kind eyes and a cheerful grin—and he was sober. "I don't mind," she had said, and they strolled in the park until night-fall, Gusev telling her about the war, raids and upheavals—things you would never find in books. He walked her home, and called on her often after that night. Masha gave herself to him simply, without fuss. And then she fell in love with him, suddenly, with every fibre of her being, feeling that he was very dear to her. That was when her anguish began.

The kettle boiled over. Masha took it off the stove and resumed her vigil. She had thought she heard a shuffling noise in the empty hall before, but had felt too forlorn and lonely to take notice of it. Now she heard it again. Someone was out there. She could hear his footsteps.

22 Masha flung the door open and looked into the hall. A number of low columns were faintly visible in the lamplight seeping in through one of the windows. Between them she saw a grey-haired old man, hatless, and wearing a long coat. He stood there glowering at her from under his knitted eyebrows, and craning his neck forward. Her knees buckled under her. "What are you doing here?" she whispered. The old man stared at her, his neck still craned forward. He raised a threatening forefinger. Masha slammed the door shut, her heart beating wildly, and listened intently to his receding steps. The old man was obviously leaving by way of the front stairs.

Soon she heard her husband's swift, vigorous stride approaching from the other end of the house. Gusev was cheerful and smudged with soot.

"Help me wash up," he said, unbuttoning his collar. "I'm leaving tomorrow! Is the kettle hot? That's fine." He washed his face, his muscular neck and his arms up to the elbows, looking at his wife out of the tail-end of his eye as he wiped himself. "Come, nothing's going to happen to me. I'll come back. If seven years of bullets and bayonets didn't get me down, my hour just isn't due—don't fret. And if I must give up the ghost, then it's in the books. Anything could finish me then, even a fly's tickle."

He sat down at the table, peeled a boiled potato, broke it in two and dipped it in salt. "Get out some clean clothes—a couple of shirts, some underwear and foot-rags. Don't forget the soap. And a needle and thread. Been crying again?"

"I was frightened," said Masha, averting her face. "There's an old man snooping about in the house. He shook his finger at me. Please don't go away, Alyosha."

"D'you mean, because an old man's been shaking his finger at you?"

"It's an ill omen."

23 "Too bad I must go—I'd have it out with the old buzzard. It's probably one of the people who lived here, stealing about nights, trying to scare the living daylights out of us." "Alyosha, will you come back to me?" "Didn't I say so? When I say a thing, I mean it." "Are you going very far?"

Gusev whistled and winked at the ceiling. His eyes danced as he poured hot tea into his saucer.

"Beyond the clouds, Masha, like the lassie up there." Masha hung her head. Gusev yawned and began to undress.

Masha cleared away the dishes noiselessly, and sat down to darn socks, scarcely daring to raise her eyes. When she took her things off and went to bed, Gusev was sound asleep, his hand resting on his chest. Masha lay down beside him and gazed at her husband. Tears coursed down her cheeks: she loved him so and yearned so for his restless heart. Where was he going? What was he after?

She rose at daybreak, brushed her husband's clothes and laid out the clean underwear. Gusev got out of bed. He drank his tea, joking and patting Masha's cheek. Then he put a big wad of money on the table, hoisted his sack over his shoulder, stood a moment in the doorway, kissed Masha, and was gone.

She never did find out from him where he was going.

THE TAKE-OFF

A little knot of gapers gathered on the lot outside Los's workshop. They I straggled in from the embankment and the Petrovsky Island, jostling and looking up every now and then at the low-hanging sun pushing its broad rays through the clouds.

"What's up? Anybody murdered?" somebody asked. "They're flying to Mars."

"Good Lord, what are we coming to?"

24 "What are you talking about? Who's flying?" "They're going to seal a couple of convicts in a steel ball and shoot it off to Mars. It's an experiment." "You're pulling my leg." "The beasts—a man's nothing to them." "Who do you mean by 'them,' may I ask?" "None of your damned business." "Inhuman, I call it." "My God, what a pack of idiots you are." "Who's an idiot?" "They ought to send you up." "Drop it, comrades. You're about to witness a signal event. Cut out your nonsense." "But what's the idea of flying to Mars?"

"Well, somebody said they're taking up 400 kilograms of propaganda leaflets." "It's an expedition." "What for?" "For gold." "That's right—to replenish our gold reserves." "How much do they expect to bring back?" "Any amount." "Citizens, how much longer do we have to wait here?" "They're taking off at sundown." The talk rippled back and forth until dusk. The people argued and quarrelled, but did not leave.

The setting sun shed a ruddy glow over half the sky. Presently a large car of the Gubernia Executive Committee nosed its way slowly through the crowd. Lights went on in the windows of the workshop. The people fell silent and pushed forward.

Open on all sides, its rows of rivets glinting, the egg-shaped spaceship stood on a slightly inclined cement platform in the middle of the shed. Its brightly-lit interior of rhomb-stitched yellow leather was visible through the open porthole.

25 Los and Gusev were clad in sheepskin jackets, felt boots and leather helmets. The members of the Executive Committee, academicians, engineers, and newspapermen surrounded the spaceship. The speechmaking was over. The photographers had taken countless shots. Los said a few words of thanks. He was pale and glassy-eyed. He embraced Khokhlov and Kuzmin. Glancing at his watch, he said: "Time we took off."

A hush fell over the crowd. Gusev frowned and crawled through the porthole. Inside, he sat on a leather seat, adjusted his helmet and straightened his jacket.

"Don't forget to see my wife!" he called out to Khokhlov, scowling hard.

Los tarried at the porthole, looking down at his feet. Suddenly he raised his head, and said in a hollow, tremulous voice:

"I think I shall make it. I'm certain that in a few years hundreds of spaceships will ply the cosmos. We shall always— always be driven by the spirit of quest. But I should not be the first to fly. I should not be the first to probe the secrets of the firmament. What will I find there? Oblivion. It is this that troubles me most as I take my leave of you. No, comrades, I'm not a genius, not a brave man, not a dreamer. I'm a coward—a fugitive."

Los broke off abruptly, and looked oddly at the people around him. They were bewildered. He pulled his helmet down over his eyes.

"But that's beside the point. My personal affairs—I'm leaving them behind, on that lonely cot in the shed. Good-bye, comrades. Stand away from the spaceship, please." Now Gusev called out from inside the cabin: "Comrades, I'll pass the Soviet Republic's warmest regards to those whatever-they are on Mars. Right?" The crowd cheered.

Los turned, crawled through the porthole and slammed the lid shut behind him. Jostling and buzzing excitedly, the people

26 pushed their way out of the shed and mixed with the crowd on the vacant lot. A voice called out warningly: "Move back and lie down."

Thousands of people stared at the lighted squares of the workshop windows. All was quiet inside, and out in the open. Several minutes elapsed. Many lay down on the ground. A horse neighed in the distance. Somebody snarled: "Silence!"

That instant the shed was shaken by an ear-splitting roar followed by a series of violent detonations. The earth shook. Out of the opening in the roof, in a cloud of smoke and dust, rose the blunt metallic nose of the spaceship. The roar grew as the craft bobbed up into the air, and hung there, as though taking aim. Then, with a thunderous din, the eight-metre sphere rocketed westward over the crowd and streaked into the reddish clouds in the distance.

The crowd came to life, shouting, throwing caps into the air, and swarming round the shed.

BLACK SKY

Los screwed the lid over the porthole, sat down, and looked into Gusev's eyes, which were as sharp and clawing as a captured bird's. "Well, Alexei Ivanovich?" "Let her go." Los grasped the lever of the rheostat, and gave it a gentle tug. There was a dull detonation—the first crash that had startled the crowd on the lot. Then he pulled a second rheostat. A dull thudding started underfoot and the spaceship vibrated so violently that Gusev clutched at his seat and rolled his eyes wildly. Los switched on both rheostats. The spaceship shot up, the vibration subsided. Los yelled:

"We're up!"

27 Gusev mopped his face. It was getting hot. The speedometer indicated 50 metres per second. Its hand kept rising.

The spaceship was speeding at a tangent in a direction opposite to the rotation of the Earth. The centrifugal force was pulling it eastwards. According to Los's calculation, the ship would straighten out at an altitude of 100 kilometres and then move along a diagonal line.

The motor worked smoothly. Los and Gusev unbuttoned their fur-lined jackets and pushed back their helmets. They turned off the electric light and sat in the pale dusk filtering in through the peep-holes.

Fighting against a sensation of weakness and dizziness, Los got down on his knees and put his eye to the peep-hole. The Earth spread out below like a huge concave bowl of blue-grey. Here and there over it, like islands, lay cloudy ridges. He was looking at the Atlantic Ocean.

Gradually the bowl grew smaller and began to drop. Its right-hand edge took on a silvery sheen, and the other edge was lost in shadows. Now it looked like a ball hurtling into an abyss. Gusev, whose eyes were glued to another peep-hole, said: "So long, old thing. We've had a long spell together—time to part." He tried to get up, lurched, and fell back into his seat.

"I'm choking, Mstislav Sergeyevich," he wheezed, tugging at his collar. "Can't breathe."

Los felt his heart beating faster and faster until it was pounding like mad. His head throbbed. Everything grew dark.

He crawled over to the speedometer. Its hand was moving rapidly, indicating an incredible velocity. The air was thinning. The gravitational pull declined. The compass showed that the Earth was directly beneath them. The ship was still picking up speed with each passing second, rocketing madly into icy space.

28 Los broke his finger-nails unbuttoning his collar. Then his heart stopped.

He had known that the ship's velocity would cause a pronounced change in the activity of the heart, in the blood circulation and the entire rhythm of the body. Knowing this, he had wired the speedometer of a gyroscope (of which there were two) to a tank which would eject a substantial dose of oxygen and ammonia at the crucial moment.

Los was the first to regain consciousness. His chest ached, his head reeled, and his heart hummed like a top. Thoughts came and went—unusual thoughts, quick and clear. His movements were light and precise.

He turned off the emergency oxygen taps and glanced at the speedometer. The spaceship was doing nearly 500 kilometres per second. A dazzling sunbeam came through one of the peep-holes and fell upon Gusev lying on his back, his teeth set in a horrible grin and his glassy eyes popping out of their sockets.

Los brought a pinch of smelling salts to his nose. Gusev took a deep breath. His eyelids fluttered. The engineer gripped him under the arm-pits and lifted him, but Gusev's body hung suspended in the air like a soap bubble. He released him, and Gusev sank slowly back to the floor. He landed with his legs outstretched and his elbows raised as if he were sitting in water. He looked about him in bewilderment. "Am I drunk?" he gasped.

Los ordered him to climb to the top peephole and look out. Gusev struggled to his feet, staggered, then crawled like a fly up the sheer wall of the cabin, clutching at its stitched leather lining. He put his eye to the peep-hole. "It's pitch dark," he reported. "I can't see a thing."

Los put a smoked eye-piece over the lens facing the sun. The sun hung suspended in space, a huge shaggy ball boldly outlined against the dark void around it. Two luminous veils of mist drifted on both sides of it like a pair of wings. A fountain spouted from the compact mass and shaped itself into a

29 mushroom. It was a period of sun spots. A little apart from the radiant ball were iridescent oceans of fire. Cast off by the sun and revolving round it, they were paler than the zodiacal wings.

Los tore himself away from the fascinating spectacle—the life-giving fire of the universe. He replaced the lid on the eyepiece. It was dark again. Then he moved to the peep-hole on the other side of the cabin. He adjusted the focus. The greenish ray of a star pricked his eye, Presently a lucid blue beam replaced it. It was Sirius, the celestial diamond, the first star of the Northern sky.

Los crawled over to the third peep-hole. He adjusted it, put his eye to it, then wiped it with his handkerchief and put his eye to it again. His heart contracted. He felt the roots of his hair twitching.

Blurred, misty spots were floating past them in the dark. "Something's out there next to us," cried Gusev in alarm. The spots drifted downward, growing distinct and bright as

they receded. Los glimpsed broken silver lines and threads, and then the boldly-etched jagged edges of a rocky ridge. The spaceship had evidently come near a celestial body, entered its gravitational field, and now begun to rotate round it like a satellite.

Los groped for the rheostat levers with a trembling hand, and pulled them as far as they would go at the risk of blowing up the ship. The engine under them shook and roared. The spots and shining jagged cliffs swiftly receded. The gleaming surface loomed larger, approaching them, and they could clearly discern sharp long shadows cast by the cliffs stretching blackly across a bare, lifeless plain.

The spaceship was heading for the rocks. Sun-bathed on one side, they seemed to be a stone's throw away. Los thought (his mind was clear and collected), "The ship will crash in a moment, before it has time to turn neck foremost to the pull of gravity. This is the end."

But just then he glimpsed the ruins of stepped towers on the dead plain between the cliffs. The ship slid over the toothy

30 crags. Beyond lay an abyss, a black void, obscurity. Metal-bearing veins glinted on the jagged side of a steep cliff. Then the fragment of the smashed, unknown planet remained far behind, continuing its journey to eternity. The spaceship was again speeding through the deserted expanse of black sky. Suddenly Gusev started: "Is that the moon ahead of us?" He turned, parted from the wall, and hung in mid- air, arms and legs spread frogwise, cursing tinder his breath, and straining to swim back to the wall. Los lost his hold on the floor, and felt himself drifting. He hung on to the ocular tube, and gazed at the glittering silvery disc of Mars.

THE DESCENT

The silvery disc of Mars, shrouded here I and there in clouds, was growing perceptibly larger. The spot of ice at the South Pole sparkled dazzlingly. Beneath it spread a curve of mist, stretching to the equator in the east, ascending in the vicinity of the prime meridian, skirting a lighter surface, and bifurcating to form a second cape at the western edge of the disc.

Five clearly visible dark dots were distributed about the equator, joined by straight lines which formed two equilateral triangles and a third elongated one. At the foot of the eastern triangle was an arc. A second semicircle ran from the middle of this arc to its extremity. Several lines, dots and semi-circles were scattered to east and west of this equatorial group. The North Pole was immersed in darkness.

Los gazed avidly at this network of lines. Here it was—the thing that drove astronomers to distraction—the ever-changing rectilinear baffling Martian canals. Los now discerned a second, barely perceptible, blurred network of lines within the bold pattern of the first.

31 He sketched the lines in his notebook. Suddenly the Martian disc pitched violently, and floated past the lens. Los leaped to the rheostats.

"We're in, Alexei Ivanovich! We're being pulled in! We're falling!"

The ship turned neck foremost to the planet. Los out down the motor, then switched it off. The change of velocity was not as painful now, but the silence that set in was so harrowing that Gusev clutched his head and pressed his hands over his ears.

Los lay on the floor watching the silvery disc grow larger and rounder. It seemed to be shooting towards them out of the void.

He switched on the rheostats. The spaceship vibrated, battling against the pull of the Martian field of gravitation. The velocity of their fall diminished. Mars shut out the sky, grew dimmer, its edges curving up like those of a bowl.

These last few moments were terrifying. They were dropping at a dizzy speed. Mars blotted out the sky. The lenses grew dim with moisture. The machine hurtled through a cloud-drift over a misty plain. Shuddering and roaring, it slowed down its descent.

"We're landing!" Los shouted, and switched off the motor. The next moment he was catapulted head over heels against the wall. The spaceship hit the ground heavily, and toppled on its side.

* * * * * * * * * *

Their knees trembled, their hands shook, and their hearts leaped wildly. Hastily and silently, Los and Gusev put the cabin in order, and stuck the half-dead mouse they had brought from the Earth out of one of the peep-holes. The mouse revived. It lifted its nose, twitched its whiskers, and washed itself. The air outside was fit for living beings.

32 They unscrewed the lid over the porthole. Los ran his tongue over his lips and said hollowly: "We've made it, Alexei Ivanovich! Out we go!"

They pulled off their felt boots and fur-lined jackets. Gusev fastened his revolver to his belt (just in case), chuckled, and swung open the lid.

MARS

The first thing they saw as they crawled out of the spaceship was the dazzling bottomless sky, deep blue as the ocean in a storm.

The sun, a great fiery ball, stood high over Mars. The stream of crystal-blue light was cool and transparent—from the startlingly vivid horizon to the zenith.

"They've a jolly sun out here," said Gusev, and sneezed, so dazzlingly bright were the deep-blue heights. There was a tightening sensation in their chests and the blood throbbed in their temples, but breathing came easy. The air was thin and dry.

The spaceship lay in an orange-coloured flat plain. The horizon was very close—almost within reach. There were large cracks in the ground. The land was overgrown with tall cactuses shaped like pronged candlesticks, which cast vivid purple shadows on the ground. A dry wind was blowing.

Los and Gusev stood looking around for a while, then set off across the plain. They found walking unusually easy, although their feet sank ankle-deep in the crumbling soil. As they skirted a tall fleshy cactus, Los touched it. It quivered, as though swayed by a gust of wind, and its brown meaty tentacles stretched towards Los's hand. Gusev kicked at its roots. The loathsome thing toppled over, driving its thorns into the sand.

33 They walked for about thirty minutes. Before them spread the same orange-coloured plain—the cactuses, the purple shadows, and the cracks in the soil. When they turned south, leaving the sun at right angles to them, Los's attention was drawn to the soil. Suddenly he stopped short, squatted on his haunches, and slapped his knee. "Alexei Ivanovich, the soil's been ploughed." "What?"

On looking closer they saw wide, crumbling grooves and straight rows of cactuses. Some steps away Gusev stumbled over a stone slab with a large bronze ring. A shred of rope was tied to the ring. Los scratched his chin. His eyes shone. "Do you know where we are?" he asked. "Yes—in a field." "And what's the ring for?" "The devil knows why they had to fix a ring in the stone." "It's to fasten a buoy. See these cockleshells? We're on the bottom of a dry canal."

"Bait," said Gusev, "they don't seem to have much water here."

They turned west and strode across the grooves. A large bird with a drooping asp-like body flew over the field, flapping its wings convulsively. Gusev stopped dead and reached for his revolver, but the bird soared, rose into the intense blue of the sky, and disappeared beyond the near horizon.

The cactuses were now taller, thicker and meatier. The men had to pick their way carefully through the quivering, thorny thicket. Animals very much like lizards, bright-orange, with scaly backs, scuttled underfoot. Strange prickly-looking balls scudded aside and leapt into the tentacled undergrowth. Los and Gusev proceeded with great care.

The cactuses terminated at the edge of a steep chalk-white bank. It was paved, apparently, with ancient hewn flagstones. Dry moss hung from the cracks and crevices. A ring like the one in the field was screwed into one of the slabs. Crested lizards lay dozing peacefully in the sun.

34 The space-travellers climbed the bank. On top, an undulating plain opened to their eyes. It was the same orange colour, but of a dimmer shade. There was a scattering of dwarfed trees, somewhat like mountain pines and white mounds of stones, and ruins. Away in the north-west rose a mountain range, as sharp and jagged as frozen tongues of flame. The summits sparkled with snow.

"We'd better get back," said Gusev. "Have a bite to eat and rest up. We'll soon fag ourselves out this way. There's not a soul around."

They lingered on the bank for a while. The plain was heart-breakingly desolate and forlorn. "What a place to come to," Gusev sighed.

They descended the bank and made for the spaceship. It took some time to find it among the cactuses. Suddenly Gusev whispered: "There it is!" He whipped his revolver out with a trained hand.

"Hey!" he shouted. "Who's meddling with our ship, you blankety-blank? I'll shoot!" "Who are you shouting at?" "See the ship over there?" "Yes, I can see it now." "There's someone on its right."

They ran, stumbling, towards the spaceship. The creature near it moved away, hopped among the cactuses, leapt high, spread its long webby wings, shot into the air with a crackling noise, and, describing, a circle over their heads, soared into the blue. It was the creature they had taken for a bird. Gusev aimed his revolver at it, but Los knocked the gun out of his hand.

"You're mad!" he cried. "Can't you see it's a Martian?" Gusev stared open-mouthed at the strange creature circling

above them in the deep-blue sky. Los pulled out his handkerchief and waved. "Take care," said Gusev. "He may plug us from up there."

"Put your revolver away, I tell you."

35 The large bird descended. Now they saw that it was a man-like, being seated in the saddle of a flying-machine. Two curved mobile wings flapped on either side, at the level of his shoulders. A disc whirred a little below the wings—a propeller apparently. Behind the saddle hung a tail with levers protruding from it. The machine was as mobile and pliant as a living being.

It dived and glided over the field with one wing up and the other down. Finally, they saw the Martian's head in an egg-shaped helmet with a tall peak. He wore goggles, and his long face was brick-red, wizened and sharp-nosed. He opened his mouth and squeaked. Then he flapped his wings rapidly, landed, ran a few steps and jumped out of his saddle some thirty paces away from the travellers.

The Martian resembled a man of medium height. He was clad in a loose yellow jacket, and his spindle legs were bound tightly above the knees. He pointed angrily at the fallen cactuses, but when Los and Gusev made a step in his direction, he jumped back into his saddle, shook his long finger at them, took off almost without a run, then landed again, shouting in a thin, squeaking voice and pointing at the broken plants.

"The block's sore at us," said Gusev. "Hey!" he cried to the Martian, "stop squeaking, you old freak! Come on over here— we don't bite!"

"Don't shout at him, Alexei Ivanovich. He doesn't know Russian. Let's sit down, or he'll never come near us."

They squatted on the sun-baked ground. Los gestured that he wanted to eat and drink. Gusev lit a cigarette and spat. The Martian regarded them for a while, ceased his chatter but still shook his long, pencil-like finger at them. Then he unfastened a bag from the saddle and threw it to them. Next he re-mounted his machine, climbed in circles to a high altitude and flew off north, where he was soon lost behind the horizon. The bag contained two metal boxes and a flat vessel filled with liquid. Gusev opened the boxes. There was a strong-smelling jelly in

36 one and a few jellied lumps, much like Turkish Delight, in the other. Gusev sniffed them.

"Ugh, so that's what they eat!" He fetched a basket of food from the spaceship, gathered a few dry cactus sticks and held a match to them. A thin wisp of smoke rose from the fire. The cactuses smouldered, but gave a great deal of heat. They warmed a tin of corned beef and laid their meal out on a clean napkin. They had not realized how ravenously hungry they were, and pitched in solidly.

The sun stood high. The wind had abated. It was hot. A small myriapod crawled up to them over the orange mounds. Gusev threw it a piece of crisped bread. Raising its triangular horny head, it froze into stony immobility.

Los asked for a cigarette and lay down, propping his cheek on his hand. He smoked and smiled.

"D'you know how long we've gone without food, Alexei Ivanovich?"

"Since yesterday, Mstislav Sergeyevich. I filled up with potatoes just before the takeoff." "No, my dear friend, we haven't eaten for 23 or 24 days." "What?!" "It was August 18 in Petrograd yesterday. Today it is September 11. Surprised?" "Surprised is not the word for it."

"I find it hard to understand myself. We took off at 7 p.m. It is 2 p.m. now. By my watch we left the Earth 19 hours ago. But if we take the clock in my ^workshop, it is almost a month. Did you ever notice how queer you feel if you wake up in a train when it stops or what an odd sensation you have if you sleep through the stop? Your body loses speed when the train stops moving. In a running train, your heart and watch both go faster than in a stationary train. True, you can hardly tell the difference, because the train's velocity is so insignificant. But our flight is another matter. We flew half the way almost at the velocity of light—and felt it only too well. As long as we were flying, our heart activity and every other motion were related,

37 and were, so to speak, part and parcel of the ship's progress. Everything moved in the same rhythm. The ship's speed was 500,000 times the normal speed of a body in motion on Earth. Hence, the speed of my heart-beats—a beat per second by the ship's watch—increased 500,000 times. This means that by the Petrograd clock my heart beat 500,000 times a second during the flight. According to my heart-beats and the ship's watch, and the way I feel, we were en route 19 hours. And so we really were— just 19 hours. But if we take the heart-beats of, someone in Petrograd, and the Petropavlovsky Church clock, more than three weeks have passed since we left the Earth. Perhaps, some day, we'll build a large spaceship, stock it with a six-month supply of food, oxygen and ultralyddite, and invite a few cranks to go up in it. 'Tired of living in our century? Want to live a hundred years from now? Get into this box and rally your patience to stay in it for six months. You will be well recompensed—considering what you'll find on your return! You'll have been gone a hundred years.' We'll shoot them into space at the speed of light. For six months they'll languish there, grow beards, then come back to Earth to find a Golden Age. That's what it'll be like."

Gusev said "oh," and "ah," and clicked his tongue in amazement.

"What d'you think of this stuff?" he asked. "Will it do us any harm?"

He pulled the stopper in the Martian flask with his teeth, tasted the liquid and spat. It was drinkable. He took a few gulps and smacked his lips. "It's something like our Madeira."

Los took a sip. The liquid was sirupy and sweet, and held the fragrance of flowers. Before they knew it half the flask was gone. A pleasant sense of ease and warmth coursed through their veins, but their minds were unclouded.

Los got to his feet and stretched himself. He felt marvellously and strangely at ease under this alien sky, as in a

38 dream. It was as though he were cast ashore by the surf of the stellar ocean—reborn to explore an unknown, new life.

Gusev stowed away the food basket in the ship, screwed the lid down on the porthole and pushed his cap back.

"I'm not a bit sorry I came, Mstislav Sergeyevich. I feel wonderful."

They decided to return to the bank and scour the hilly plain until dark.

In the highest of spirits they made their way among the cactuses, clearing them now and then with long, bouncy leaps. Soon they glimpsed the flagstones gleaming white through the thickets.

Suddenly Los stopped. His skin crept with loathing. Staring up at him from behind meaty cactus leaves some three paces away was a. pair of eyes, as large as those of a horse, with drooping red eyelids. There was intense, deadly hatred in their piercing glare.

"What's the matter?" Gusev asked. Then he saw them too. He fired his revolver at once. There was a spurt of dust, and the eyes disappeared. "There's another!" Gusev turned and fired at a striped brown fat body moving swiftly on long, spidery legs. It was the kind of giant spider that is to be found on Earth on the bottom of deep oceans. It escaped into the thickets.

THE DESERTED HOUSE

From the canal bank to the nearest copse Los and Gusev walked in brown-baked dust, clearing dry ditches, and shirting ponds. Here and there, the rusty skeletons of what used to be barges jutted out of the sand of the abandoned canal beds. Convex discs a metre in diameter gleamed in the dead, dismal plain. They stretched in a line of glimmering dots from the craggy mountains down to the thickets and ruins below.

39 A clump of stunted brown trees with spreading flat crowns and gnarled branches nestled between two hills. Their foliage was moss-like, their trunks knotted and veined. Shreds of barbed netting were stretched between the outermost trees.

They entered the copse. Gusev stooped and kicked something in the dust. A fractured human skull rolled out. Metal gleamed in its teeth. It was hot there. The mossy branches offered meagre shelter from the blazing rays of the sun. A few steps away they stumbled upon one of the convex discs; it was attached to the edge of a round metal well. Then, at the back of the copse, they came upon the ruins of a thick brick wall. Mounds of rubble and twisted metal beams lay around it.

"These houses were blown up," Gusev observed. "They've been fighting. I've seen plenty of this sort of thing before."

A giant spider appeared from behind a heap of rubble and ran along the jagged edge of a wall. Gusev fired. The spider leaped high and toppled over. Another came running out of the ruins and made for the trees, raising little clouds of brown dust. It ran into the barbed netting and struggled vainly to extricate itself.

Gusev and Los came to a hill-top and descended in the direction of another little copse, in which they glimpsed a few brick structures around a tall flat-roofed stone building. There were several discs between the hill and the buildings. Pointing at them, Los said:

"They're probably the wells of a water main, complete with pneumatic piping and electric wiring. Seems they've been out of use for years."

They cleared the barbed netting, crossed' the copse, and approached a sprawling-flagged courtyard. At its far end stood a house of unique) sombre architecture. Its smooth walls tapered towards a massive cornice of black and red stone. The windows, set deep in the walls, were long and narrow as crevices. Two corrugated tapering pillars supported a portal with a bronze bas-relief depicting a reclining figure with closed

40 eyes. Flat steps running the length of the facade led up to a low massive door. Wilted fibres of creeping plants hung between the dark slabs of the wall. The building resembled a huge tomb.

Gusev put his shoulder to the metal door and heaved. It gave way with a creak. They passed a dark vestibule and entered a large hall. Light filtered in through a glass dome. The hall was almost empty. There were a few upturned stools and a low table covered-with a dusty black cloth. The stone floor was littered with broken crockery, and a strange kind of machine or instrument made of discs, globes and metal netting stood near the door. Everything was coated with dust.

Dusty shafts of light fell on the yellowish-gold-specked walls, which were fringed with a wide strip of mosaic, depicting, apparently historical episodes—battles between yellow-skinned and red-skinned creatures; a manlike figure immersed up to the waist in the sea; the same figure flying amid the stars; battle scenes and scenes of combat with beasts of prey; herds of strange-looking animals driven by shepherds; scenes of domestic life; hunting scenes; dances; birth and death rituals. The dismal mosaic terminated over the doorway in a picture of a giant circular reservoir.

"Most interesting," said Los, stepping on to a couch for a closer look at the mosaic. "A strange human head keeps recurring in all the scenes. What can it mean?"

In the meantime, Gusev discovered a door which opened on to an inner stairway. It led to a broad arched passage flooded with dust-laden light.

All along the walls and in the niches stood stone and bronze figures, busts, heads, masks, fragments of vases. Marble and bronze doorways led to private chambers.

Gusev decided to investigate the low-ceilinged, musty and dimly-lit rooms. In one of them he found an empty swimming pool, on the bottom of which lay a dead spider. In another a smashed mirror ran the length and breadth of one of the walls. On the floor lay a pile of rotting rags and upturned furniture; in the closets hung decayed remnants of various garments.

41 In the third room a wide couch stood upon a dais under a skylight. The skeleton of a Martian hung from the couch to the floor. The place bore traces of fierce fighting. A second skeleton lay huddled in a corner.

Amid the rubbish Gusev found several coined metal objects, much like women's ornaments, and little vessels of coloured stone. From among the rotting tatters that were once the garments of one of the skeletons, he picked up two large dark-gold stones joined by a miniature chain. The stones glowed warmly.

"They'll come in handy," Gusev muttered to himself. "I'll give them to Masha."

Los stopped to examine the sculptures in the passage. Among the sharp-nosed Martian heads, statues of sea monsters, painted masks, and vases, whose shapes and ornaments were curiously like those of the Etruscan anaphoras, his eye picked out a large statue of a naked woman with tousled hair and a savage assymetrical face. Her breasts were pointed and far apart. She wore a golden tiara of stars, which formed a thin parabola on her forehead. It was inlaid with two little balls— one ruby-red, and the other brick-red. The sensuous haughty face was strangely familiar.

Beside the statue was a dark niche fenced off with a netted screen. Los dug his fingers through the netting, but it would not give way. He lit a match and peered in. A golden mask lay on the remnants of a cushion. It was the mask of a human face with high cheek-bones and serenely closed eyes. The crescent-shaped mouth was smiling. The nose was pointed, like a bird's beak. A swelling between the eyebrows had the shape of a large dragon-fly's eye. It was the head he had seen on the mosaic strip in the first hall. Los burned half his matches examining the curious mask. Shortly before his departure from the Earth, he had seen photographs of similar masks, discovered among ruins of giant cities on the Niger, in the part of Africa where signs of an extinct culture suggested a race mysteriously vanished.

42 One of the side doors in the passage was ajar. Los entered a long high-ceilinged room with a gallery and latticed balustrade. Below the gallery, and on it, were bookcases and shelves with fat volumes. Their backs, stamped in gold, lined the grey walls. There were small metal cylinders in some of the bookcases, and leather- or wood-bound volumes. From the bookcases, shelves, and the dark corners blindly stared busts of wizened, bald-headed Martian scientists. Several deep seats and cabinets on spindle legs with round screens attached to their sides stood about the room.

Los surveyed this mildewed treasure-house with bated breath. Its books contained the wisdom of centuries. He approached a shelf and carefully pulled out a book. Its pages were greenish, and the letters shaped like geometric figures coloured a light-brown hue. He put one of the books with technical drawings into his pocket, to study it closer at his leisure. The metal receptacles contained yellow cylinders resembling phonograph records of old. At the scratch of a finger-nail they sounded like bone, but their surface was as smooth as glass. He saw one of them on the top of a screened cabinet. Someone had apparently been about to use it when the house was attacked.