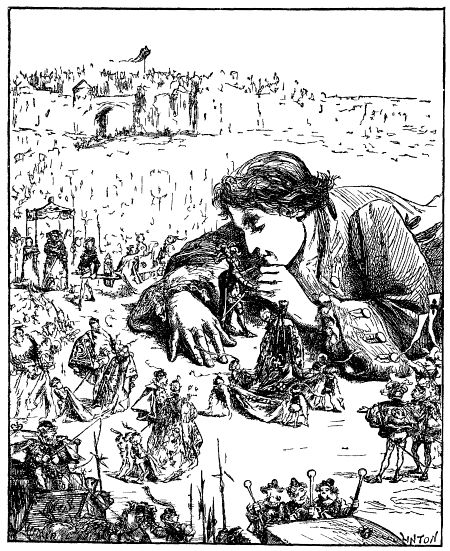

When Bastian happens upon an old book called The Neverending Story, he's swept into the magical world of Fantastica--so much that he finds he has actually become a character in the story! And when he realizes that this mysteriously enchanted world is in great danger, he also discovers that he is the one chosen to save it. Can Bastian overcome the barrier between reality and his imagination in order to save Fantastica?

THIS EPIC WORK of the imagination has captured the hearts of millions of readers worldwide since it was first published more than a decade ago. Its special story within a story is an irresistible invitation for readers to become part of the book itself. And now this modern classic and bibliophiles dream is available in hardcover again.

The story begins with a lonely boy named Bastian and the strange book that draws him into the beautiful but doomed world of Fantastica. Only a human can save this enchanted place—by giving its ruler, the Childlike Empress, a new name. But the journey to her tower leads through lands of dragons, giants, monsters, and magic—and once Bastian begins his quest, he may never return. As he is drawn deeper into Fantastica, he must find the courage to face unspeakable foes and the mysteries of his own heart.

Readers, too, can travel to the wondrous, unforgettable world of Fantastica if they will just turn the page....

Jacket illustration © Dan Craig, 1997

Copyright © 1979 by K. Thienemanns Verlag, Stutgart Translation Copy right © 1983 by Doubleday & Company. Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording,or

any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in

connection with a review for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

CIP Data is available.

This edition published in the United States 1997 by Dutton's Children's Books,

a division of Penguin Books USA INC.

357 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

First published in Germany 1979 as Die unendliche Geschichte by

- Thienemanns Verlag

This translation first published in the United States of America 1983 by Doubleday & Company, Inc. and by Penguin Books 1984

Display typography by Semadar Megged Printed in the U.S.A.

First Edition ISBN 0-525-45758-5

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

ePub created by Orannis 2011

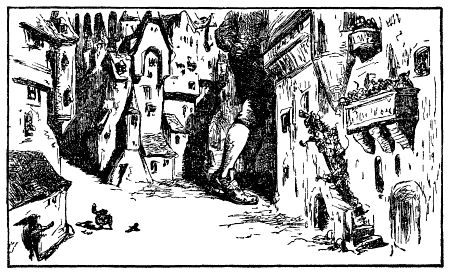

This inscription could be seen on the glass door of a small shop, but naturally this was only the way it looked if you were inside the dimly lit shop, looking out at the street through the plate-glass door.

Outside, it was a gray, cold, rainy November morning. The rain ran down the glass and over the ornate letters. Through the glass there was nothing to be seen but the rain-splotched wall across the street.

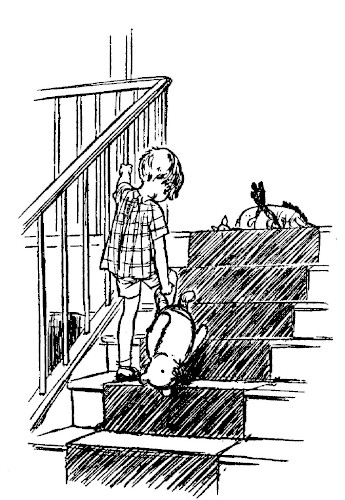

Suddenly the door was opened so violently that a little cluster of brass bells tinkled wildly, taking quite some time to calm down. The cause of this hubbub was a fat little boy of ten or twelve. His wet, dark-brown hair hung down over his face, his coat was soaked and dripping, and he was carrying a school satchel slung over his shoulder.

He was rather pale and out of breath, but, despite the hurry he had been in a moment before, he was standing in the open doorway as though rooted to the spot.

Before him lay a long, narrow room, the back of which was lost in the half- light. The walls were lined with shelves filled with books of all shapes and sizes. Large folios were piled high on the floor, and on several tables lay heaps of smaller, leather-bound books, whose spines glittered with gold. The far end of the room was blocked off by a shoulder-high wall of books, behind which the light of a lamp could be seen. From time to time a ring of smoke rose up in the lamplight, expanded, and vanished in darkness. One was reminded of the smoke signals that Indians used for sending news from hilltop to hilltop. Apparently someone was sitting there, and, sure enough, the little boy heard a cross voice from behind the wall of books: “Do your wondering inside or outside, but shut the door. There’s a draft.”

The boy obeyed and quietly shut the door. Then he approached the wall of books and looked cautiously around the corner. There, in a high worn leather wing chair sat a short, stout man in a rumpled black suit that looked frayed and somehow dusty. His paunch was held in by a vest with a flower design. He was bald except for outcroppings of white hair over his ears. His red face suggested a vicious bulldog. A gold-rimmed pince-nez was perched on his bulbous nose. He was smoking a curved pipe, which dangled from one corner of his mouth and pulled his whole cheek out of shape. On his lap he held a book, which he had evidently been reading, for in closing it he had left the thick forefinger of his left hand between the leaves as a kind of bookmark.

With his right hand he now removed his spectacles and examined the fat little boy, who stood there dripping. After a while, the man narrowed his eyes, which made him look more vicious than ever, and muttered: “Goodness gracious.” Then he opened his book and went on reading.

The little boy didn’t know quite what to do, so he just stood there, gaping. Finally the man closed his book—as before, with his finger between the pages— and growled: “Listen, my boy, I can’t abide children. I know it’s the style nowadays to make a terrible fuss over you—but I don’t go for it. I simply have no use for children. As far as I’m concerned, they’re no good for anything but screaming, torturing people, breaking things, smearing books with jam and tearing the pages. It never dawns on them that grown-ups may also have their troubles and cares. I’m only telling you this so you’ll know where you’re at. Anyway, I have no children’s books and I wouldn’t sell you the other kind. So now we understand each other, I hope!”

After saying all this without taking his pipe out of his mouth, he opened his book again and went on reading.

The boy nodded silently and turned to go, but somehow he felt that he couldn’t take this last remark lying down. He turned around and said softly: “ All children aren’t like that.”

Slowly the man looked up and again removed his spectacles. “You still here? What must one do to be rid of you? And what was this terribly important thing you had to tell me?”

“It wasn’t terribly important,” said the boy still more softly. “I only wanted

. . . to say that all children aren’t the way you said.”

Really?” The man raised his eyebrows in affected surprise. “Then you must be the big exception, I presume?”

The fat boy didn’t know what to say. He only shrugged his shoulders a little,

and turned to go.

“And anyway,” he heard the gruff voice behind him, “where are your manners? If you had any, you’d have introduced yourself.”

“My name is Bastian,” said the boy. “Bastian Balthazar Bux.”

“That’s a rather odd name,” the man grumbled. “All those B ’s. Oh well, you can’t help it. You didn’t choose it. My name is Carl Conrad Coreander.”

“That makes three C’ s.”

“Hmm,” the man grumbled. “Quite right.”

He puffed a few clouds. “Oh well, our names don’t really matter, as we’ll never see each other again. But before you leave, there’s just one thing I’d like to know: What made you come bursting into my shop like that? It looked to me as if you were running away from something. Am I right?”

Bastian nodded. Suddenly his round face was a little paler than before and his eyes a little larger.

“I suppose you made off with somebody’s cashbox,” Mr. Coreander conjectured, “or knocked an old woman down, or whatever little scamps like you do nowadays. Are the police after you, boy?”

Bastian shook his head.

“Speak up,” said Mr. Coreander. “Whom were you running away from?” “The others.”

“What others?”

“The children in my class.” “Why?”

“They won’t leave me alone.” “What do they do to you?”

“They wait for me outside the schoolhouse.” “And then what?”

“Then they shout all sorts of things. And push me around and laugh at me.” “And you just put up with it?”

Mr. Coreander looked at the boy for a while disapprovingly. Then he asked: “Why don’t you just give them a punch on the nose?”

Bastian gaped. “No, I wouldn’t want to do that. And besides, I can’t box.” “How about wrestling?” Mr. Coreander asked. “Or running, swimming,

football, gymnastics? Are you no good at any of them?” The boy shook his head.

“In other words,” said Mr. Coreander, “you’re a weakling.” Bastian shrugged his shoulders.

“But you can still talk,” said Mr. Coreander. “Why don’t you talk back at them when they make fun of you?”

“I tried . . .”

“Well . . .?”

“They threw me into a garbage can and tied the lid on. I yelled for two hours before somebody heard me.”

“Hmm,” Mr. Coreander grumbled. “And now you don’t dare?” Bastian nodded.

“In that case,” Mr. Coreander concluded, “you’re a scaredy-cat too.” Bastian hung his head.

“And probably a hopeless grind? Best in the class, teacher’s pet? Is that it?” “No,” said Bastian, still looking down. “I was put back last year.”

“Good Lord!” cried Mr. Coreander. “A failure all along the line.”

Bastian said nothing, he just stood there in his dripping coat. His arms hung limp at his sides.

“What kind of things do they yell when they make fun of you?” Mr.

Coreander wanted to know. “Oh, all kinds.”

“For instance?”

“Namby Pamby sits on the pot. The pot cracks up, says Namby Pamby: I guess it’s ‘cause I weigh a lot!”

“Not very clever,” said Mr. Coreander. “What else?”

Bastian hesitated before listing: “Screwball, nitwit, braggart, liar . . .” “Screwball? Why do they call you that?”

“I talk to my self sometimes.” “What kind of things do you say?”

“I think up stories. I invent names and words that don’t exist. That kind of thing.”

“And you say these things to yourself? Why?” “Well, nobody else would be interested.”

Mr. Coreander fell into a thoughtful silence. “What do your parents say about this?”

Bastian didn’t answer right away. After a while he mumbled: “Father doesn’t say anything. He never says anything. It’s all the same to him.”

“And your mother?” “She—she’s gone.”

“Your parents are divorced?”

“No,” said Bastian. “She’s dead.”

At that moment the telephone rang. With some difficulty Mr. Coreander pulled himself out of his armchair and shuffled into a small room behind the shop. He picked up the receiver and indistinctly Bastian heard him saying his name. After that there was nothing to be heard but a low mumbling.

Bastian stood there. He didn’t quite know why he had said all he had and admitted so much. He hated being questioned like that. He broke into a sweat as it occurred to him that he was already late for school. He’d have to hurry, oh yes, he’d have to run—but he just stood there, unable to move. Something held him fast, he didn’t know what.

He could still hear the muffled voice from the back room. It was a long telephone conversation.

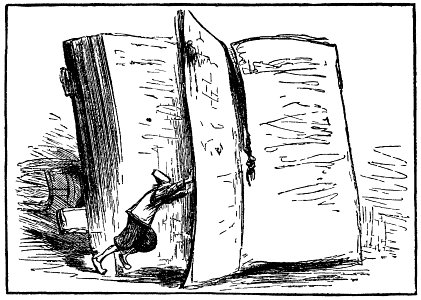

It came to Bastian that he had been staring the whole time at the book that Mr. Coreander had been holding and that was now lying on the armchair. He couldn’t take his eyes off it. It seemed to have a kind of magnetic power that attracted him irresistibly.

He went over to the chair, slowly held out his hand, and touched the book. In that moment something inside him went click! , as though a trap had shut. Bastian had a vague feeling that touching the book had started something irrevocable, which would now take its course.

He picked up the book and examined it from all sides. It was bound in copper- colored silk that shimmered when he moved it about. Leafing through the pages, he saw the book was printed in two colors. There seemed to be no pictures, but there were large, beautiful capital letters at the beginning of the chapters. Examining the binding more closely, he discovered two snakes on it, one light and one dark. They were biting each other’s tail, so forming an oval. And inside the oval, in strangely intricate letters, he saw the title:

The Neverending Story

Human passions have mysterious ways, in children as well as grown-ups. Those affected by them can’t explain them, and those who haven’t known them have no understanding of them at all. Some people risk their lives to conquer a mountain peak. No one, not even they themselves, can really explain why. Others ruin themselves trying to win the heart of a certain person who wants nothing to do with them. Still others are destroyed by their devotion to the pleasures of the table. Some are so bent on winning a game of chance that they lose everything they own, and some sacrifice every thing for a dream that can never come true. Some think their only hope of happiness lies in being somewhere else, and spend their whole lives traveling from place to place. And some find no rest until they have become powerful. In short, there are as many different passions as there are people.

Bastian Balthazar Bux’s passion was books.

If you have never spent whole afternoons with burning ears and rumpled hair, forgetting the world around you over a book, forgetting cold and hunger—

If you have never read secretly under the bedclothes with a flashlight, because your father or mother or some other well-meaning person has switched off the lamp on the plausible ground that it was time to sleep because you had to get up so early—

If you have never wept bitter tears because a wonderful story has come to an end and you must take your leave of the characters with whom you have shared so many adventures, whom you have loved and admired, for whom you have hoped and feared, and without whose company life seems empty and meaningless—

If such things have not been part of your own experience, you probably won’t understand what Bastian did next.

Staring at the title of the book, he turned hot and cold, cold and hot. Here was just what he had dreamed of, what he had longed for ever since the passion for books had taken hold of him: A story that never ended! The book of books!

He had to have this book—at any price.

At any price? That was easily said. Even if he had had more to offer than the bit of pocket money he had on him—this cranky Mr. Coreander had given him clearly to understand that he would never sell him a single book. And he certainly wouldn’t give it away. The situation was hopeless.

Yet Bastian knew he couldn’t leave without the book. It was clear to him that he had only come to the shop because of this book. It had called him in some mysterious way, because it wanted to be his, because it had somehow always belonged to him.

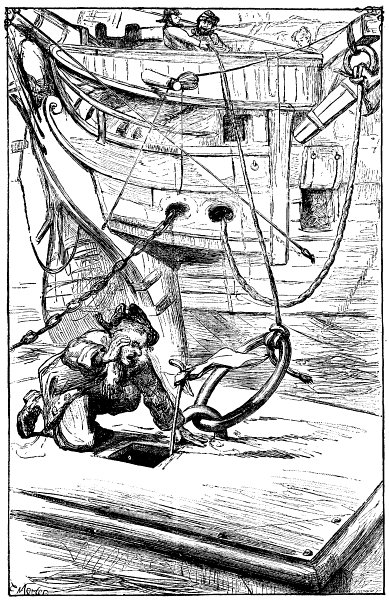

Bastian listened to the mumbling from the little back room. In a twinkling, before he knew it, he had the book under his coat and was hugging it with both arms. Without a sound he backed up to the street door, keeping an anxious eye on the other door, the one leading to the back room. Cautiously he turned the door handle. To keep the brass bells from ringing, he opened the glass door just wide enough for him to slip through. He quietly closed the door behind him.

Only then did he start running.

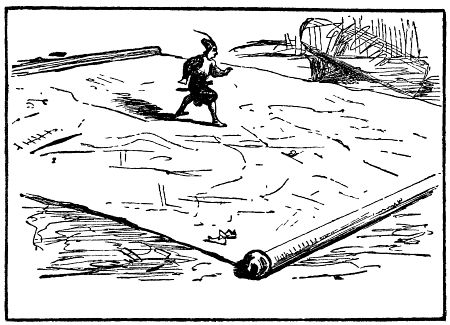

The books, copybooks, pens and pencils in his satchel jiggled and rattled to the rhythm of his steps. He had a stitch in his side. But he kept on running.

The rain ran down his face and into his collar. The wet cold passed through his coat, but Bastian didn’t feel it. He felt hot all over, but not from running.

His conscience, which hadn’t let out a peep in the bookshop, had suddenly woken up. All the arguments that had seemed so convincing melted away like snowmen under the fiery breath of a dragon.

He had stolen. He was a thief!

What he had done was worse than common theft. That book was certainly the only one of its kind and impossible to replace. It was surely Mr. Coreander’s greatest treasure. Stealing a violinist’s precious violin or a king’s crown wasn’t at all the same as filching money from a cash drawer.

As he ran, he hugged the book tight under his coat. Regardless of what this book might cost him, he couldn’t bear to lose it. It was all he had left in the world.

Because naturally he couldn’t go home anymore.

He tried to imagine his father at work in the big room he had furnished as a laboratory. Around him lay dozens of plaster casts of human teeth, for his father was a dental technician. Bastian had never stopped to ask himself whether his father enjoyed his work. It occurred to him now for the first time, but now he would never be able to ask him.

If he went home now, his father would come out of his lab in a white smock, possibly holding a plaster cast, and he would ask: “Home so soon?” “Yes,” Bastian would answer. “No school today?” He saw his father’s quiet, sad face, and he knew he couldn’t possibly lie to him. Much less could he tell him the truth. No, the only thing left for him was to go away somewhere. Far, far away.

His father must never find out that his son was a thief. And maybe he wouldn’t even notice that Bastian wasn’t there anymore. Bastian found this thought almost comforting.

He had stopped running. Walking slowly, he saw the schoolhouse at the end of the street. Without thinking, he was taking his usual route to school. He passed a few people here and there, yet the street seemed deserted. But to a schoolboy arriving very, very late, the world around the schoolhouse always seems to have gone dead. At every step he felt the fear rising within him. Under the best of circumstances he was afraid of school, the place of his daily defeats, afraid of his teachers, who gently appealed to his conscience or made him the butt of their rages, afraid of the other children, who made fun of him and never missed a chance to show him how clumsy and defenseless he was. He had always thought of his school years as a prison term with no end in sight, a misery that would continue until he grew up, something he would just have to live through.

But when he now passed through the echoing corridors with their smell of floor wax and wet overcoats, when the lurking stillness suddenly stopped his ears like cotton, and when at last he reached the door of his classroom, which was painted the same old spinach color as the walls around it, he realized that this, too, was no place for him. He would have to go away. So he might as well go at once.

But where to?

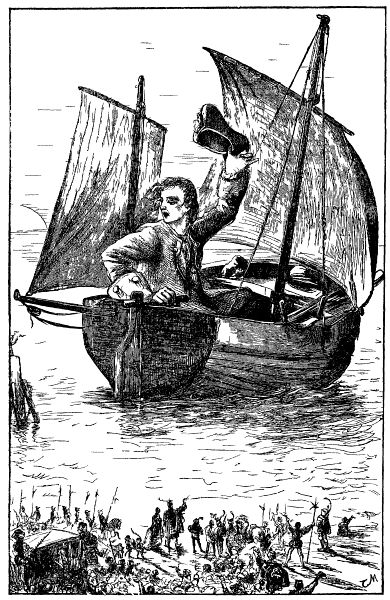

Bastian had read stories about boys who ran away to sea and sailed out into the world to make their fortune. Some became pirates or heroes, others grew rich and when they returned home years later no one could guess who they were.

But Bastian didn’t feel up to that kind of thing. He couldn’t conceive of anyone taking him on as a cabin boy. Besides, he had no idea how to reach a seaport with suitable ships for such an undertaking.

So where could he go?

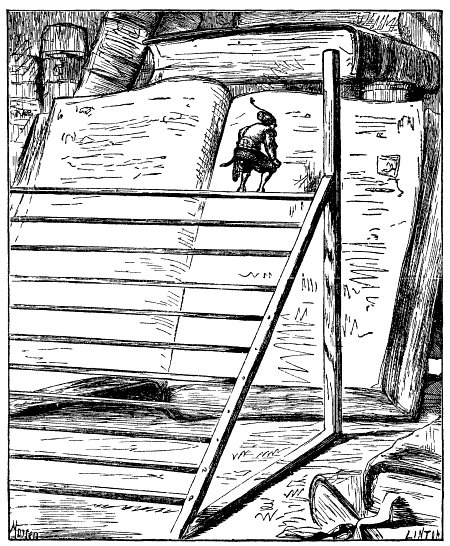

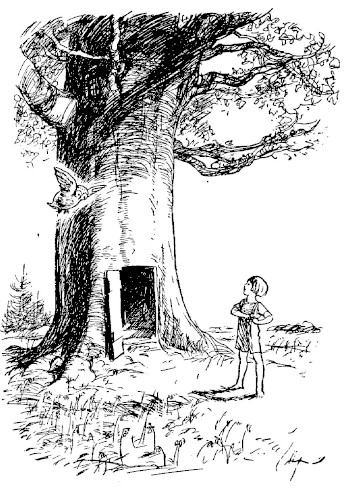

Suddenly he thought of the right place, the only place where—at least for the time being—no one would find him or even look for him.

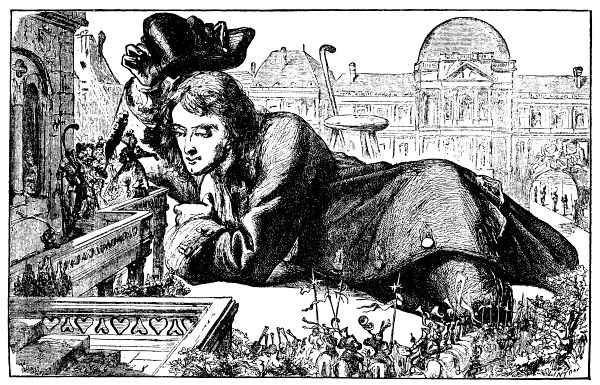

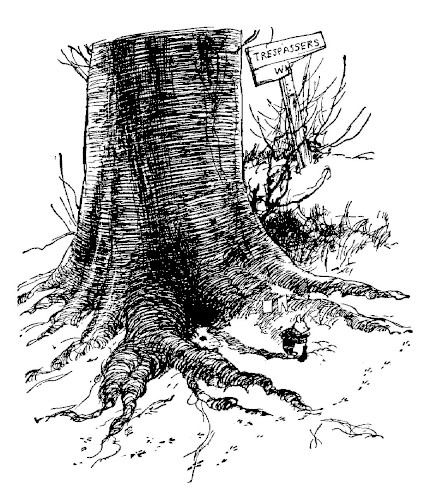

The attic of the school was large and dark. It smelled of dust and mothballs. Not a sound to be heard, except for the muffled drumming of the rain on the enormous tin roof. Great beams blackened with age rose at regular intervals from the plank floor, joined with other beams at head height, and lost themselves in the darkness. Here and there spider webs as big as hammocks swayed gently in the air currents. A milky light fell from a skylight in the roof.

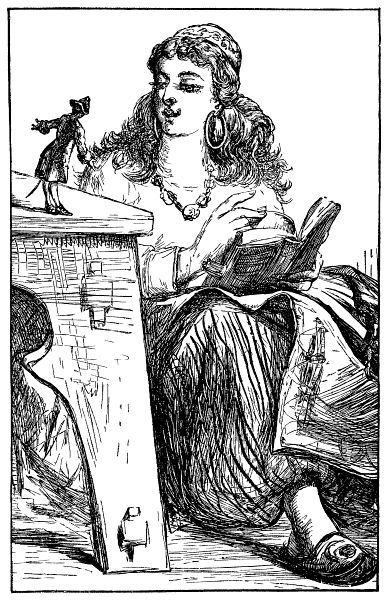

The one living thing in this place where time seemed to stand still was a little

mouse that came hobbling across the floor, leaving tiny footprints in the dust— and between them a fine line, a tailprint. Suddenly it stopped and pricked up its ears. And then it vanished— whoosh! —into a hole in the floor.

The mouse had heard the sound of a key in a big lock. The attic door opened slowly, with a loud squeak. For a moment a long strip of light crossed the room. Bastian slipped in. Then, again with a squeak, the door closed. Bastian put the big key in the lock from inside and turned it. Then he pushed the bolt and heaved a sigh of relief. Now no one could possibly find him. No one would look for him here. The place was seldom used—he was pretty sure of that—and even if by chance someone had something to do in the attic, today or tomorrow, he would simply find the door locked. And the key would be gone. And even if they somehow got the door open, Bastian would have time to hide behind the junk that was stored here.

Little by little, his eyes got used to the dim light. He knew the place. Some months before, he had helped the janitor to carry a laundry basket full of old copybooks up here. And then he had seen where the key to the attic door was kept—in a wall cupboard next to the topmost flight of stairs. He hadn’t thought of it since. But today he had remembered.

Bastian began to shiver, his coat was soaked through and it was cold in the attic. The first thing to do was find a place where he could make himself more or less comfortable, because he took it for granted that he’d have to stay here a long time. How long? The question didn’t enter his head, nor did it occur to him that he would soon be hungry and thirsty.

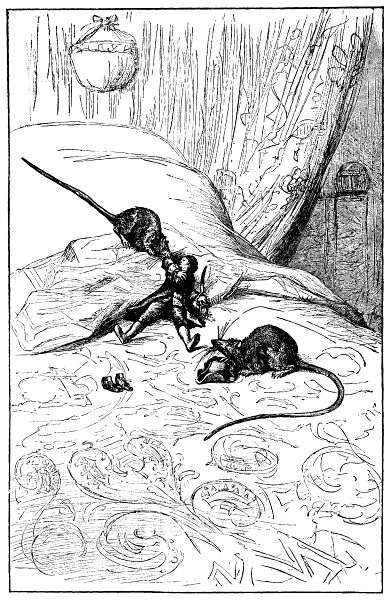

He looked around for a while. The place was crammed with junk of all kinds; there were shelves full of old files and records, benches and ink-stained desks were heaped up every which way, a dozen old maps were hanging on an iron frame, there were blackboards that had lost a good deal of their black, and cast- iron stoves, broken-down pieces of gymnasium equipment—including a horse with the stuffing coming out through the cracks in its hide—and a number of soiled mats. There were also quite a few stuffed animals—at least what the moths had left of them—a big owl, a golden eagle, a fox, and so on, cracked retorts and other chemical equipment, a galvanometer, a human skeleton hanging on a clothes rack, and a large number of cartons full of old books and papers. Bastian finally decided to make his home on the pile of old gym mats. When he stretched out on them, it was almost like lying on a sofa. He dragged them to the place under the skylight where the light was best. Not far away he found a pile of gray army blankets; they were dusty and ragged but that didn’t matter now.

He carried them over to his nest. He took off his wet coat and hung it on the clothes rack beside the skeleton. The skeleton jiggled and swayed, but Bastian had no fear of it, maybe because he was used to such things at home. He also removed his wet shoes. In his stocking feet he squatted down on the mats and wrapped himself in the gray blankets like an Indian. Beside him lay his school satchel—and the copper-colored book.

It passed through his mind that the rest of them down in the classroom would be having history just then. Maybe they’d be writing a composition on some deadly dull subject.

Bastian looked at the book.

“I wonder,” he said to himself, “what’s in a book while it’s closed. Oh, I know it’s full of letters printed on paper, but all the same, something must be happening, because as soon as I open it, there’s a whole story with people I don’t know yet and all kinds of adventures and deeds and battles. And sometimes there are storms at sea, or it takes you to strange cities and countries. All those things are somehow shut up in a book. Of course you have to read it to find out. But it’s already there, that’s the funny thing. I just wish I knew how it could be.”

Suddenly an almost festive mood came over him.

He settled himself, picked up the book, opened it to the first page, and began to read

The Neverending Story

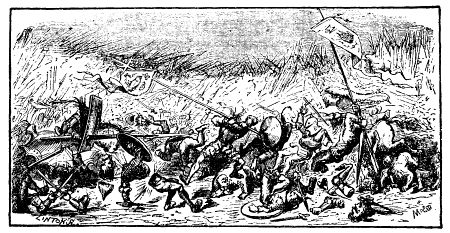

ll the beasts in Howling Forest

were safe in their caves, nests, and burrows.

It was midnight, the storm wind was whistling through the tops of the great ancient trees. The towering trunks creaked and groaned.

Suddenly a faint light came zigzagging through the woods, stopped here and there, trembling fitfully, flew up into the air, rested on a branch, and a moment later hurried on. It was a glittering sphere about the size of a child’s ball; it moved in long leaps, touched the ground now and then, then bounded up again. But it wasn’t a ball.

It was a will-o’-the-wisp. It had lost its way. And that’s something quite unusual even in Fantastica, because ordinarily will-o’-the-wisps make others lose their way.

Inside this ball of light there was a small, exceedingly active figure, which ran and jumped with all its might. It was neither male nor female, for such distinctions don’t exist among will-o’-the-wisps. In its right hand it carried a tiny

white flag, which glittered behind it. That meant it was either a messenger or a flag-of-truce bearer.

You’d think it would have bumped into a tree, leaping like that in the darkness, but there was no danger of that, for will-o’-the-wisps are incredibly nimble and can change directions in the middle of a leap. That explains the zigzagging, but in a general sort of way it moved in a definite direction.

Up to the moment when it came to a jutting crag and started back in a fright.

Whimpering like a puppy, it sat down on the fork of a tree and pondered awhile before venturing out and cautiously looking around the crag.

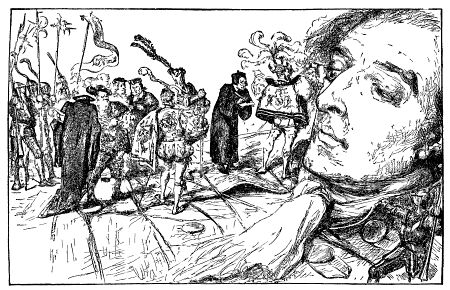

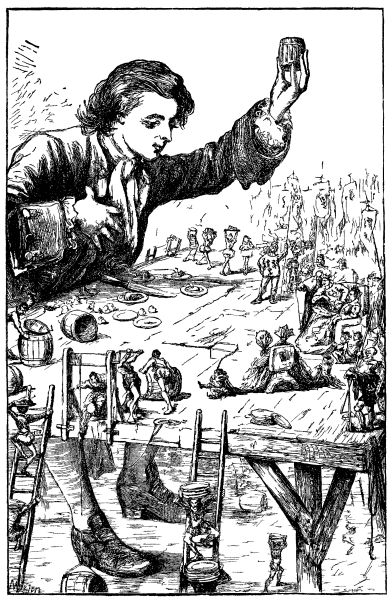

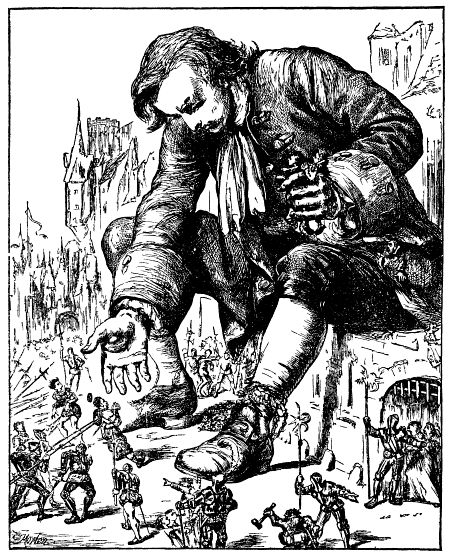

Up ahead it saw a clearing in the woods, and there in the light of a campfire sat three figures of different sizes and shapes. A giant, who looked as if the whole of him were made of gray stone, lay stretched out on his belly. He was almost ten feet long. Propped up on one elbow, he was looking into the fire. In his weather-beaten stone face, which seemed strangely small in comparison with his powerful shoulders, his teeth stood out like a row of steel chisels. The will- o’-the-wisp recognized him as belonging to the family of rock chewers. These were creatures who lived in a mountain range inconceivably far from Howling Forest—but they not only lived in the mountain range, they also lived on it, for little by little they were eating it up. Rocks were their only food. Luckily a little went a long way. They could live for weeks and months on a single bite of this— for them—extremely nutritious fare. There weren’t very many rock chewers, and besides it was a large mountain range. But since these giants had been there a long time—they lived to a greater age than most of the inhabitants of Fantastica

—those mountains had come, over the years, to look very strange—like an enormous Swiss cheese, full of holes and grottoes. And that is why they were known as the Cheesiewheezies.

But the rock chewers not only fed on stone, they made everything they needed out of it: furniture, hats, shoes, tools, even cuckoo clocks. So it was not surprising that the vehicle of this particular giant, which was now leaning against a tree behind him, was a sort of bicycle made entirely of this material, with two wheels that looked like enormous millstones. On the whole, it suggested a steamroller with pedals.

The second figure, who was sitting to the right of the first, was a little night- hob.

No more than twice the size of the will-o’-the-wisp, he looked like a pitch- black, furry caterpillar sitting up. He had little pink hands, with which he gestured violently as he spoke, and below his tousled black hair two big round

eyes glowed like moons in what was presumably his face.

Since there were night-hobs of all shapes and sizes in every part of Fantastica, it was hard to tell by the sight of him whether this one had come from far or near. But one could guess that he was traveling, because the usual mount of the night-hobs, a large bat, wrapped in its wings like a closed umbrella, was hanging head-down from a nearby branch.

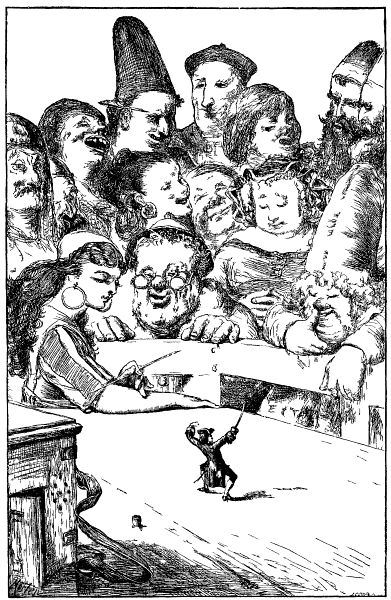

It took the will-o’-the-wisp some time to discover the third person on the left side of the fire, for he was so small as to be scarcely discernible from that distance. He was one of the tinies, a delicately built little fellow in a bright- colored suit and a top hat.

The will-o’-the-wisp knew next to nothing about tinies. But it had once heard that these people built whole cities in the branches of trees and that the houses were connected by stairways, rope ladders, and ramps. But the tinies lived in an entirely different part of the boundless Fantastican Empire, even farther away than the rock chewers. Which made it all the more amazing that the mount which had evidently carried the tiny all this way was, of all things, a snail. Its pink shell was surmounted by a gleaming silver saddle, and its bridle, as well as the reins fastened to its feelers, glittered like silver threads.

The will-o’-the-wisp couldn’t get over it that three such different creatures should be sitting there so peacefully, for harmony between different species was by no means the rule in Fantastica. Battles and wars were frequent, and certain of the species had been known to feud for hundreds of years. Moreover, not all the inhabitants of Fantastica were good and honorable, there were also thieving, wicked, and cruel ones. The will-o’-the-wisp itself belonged to a family that was hardly reputed for truthfulness or reliability.

After observing the scene in the firelight for some time, the will-o’-the-wisp noticed that each of the three had something white, either a flag or a white scarf worn across his chest. Which meant that they were messengers or flag-of-truce bearers, and that of course accounted for the peaceful atmosphere.

Could they be traveling on the same business as the will-o’-the-wisp?

What they were saying couldn’t be heard from a distance because of the howling wind in the treetops. But since they respected one another as messengers, mightn’t they recognize the will-o’-the-wisp in the same capacity and refrain from harming him? It had to ask someone the way, and there seemed little likelihood of finding a better opportunity at this hour in the middle of the woods. So plucking up courage, it ventured out of its hiding place and hovered trembling in mid-air, waving its white flag.

The rock chewer, whose face was turned in that direction, was first to notice the will-o’-the-wisp.

“Lots of traffic around here tonight,” he crackled. “Here comes another one.” “Hoo, it’s a will-o’-the-wisp,” whispered the night-hob, and his moon eyes

glowed. “Pleased to meet you!”

The tiny stood up, took a few steps toward the newcomer, and chirped: “If my eyes don’t deceive me, you are here as a messenger.”

“Yes indeed,” said the will-o’-the-wisp.

The tiny removed his red top hat, made a slight bow, and twittered: “Oh, do join us. We, too, are messengers. Won’t you be seated?”

And with his hat he motioned toward an empty place by the fire. “Many thanks,” said the will-o’-the-wisp, coming timidly closer. “Allow me to introduce myself. My name is Blubb.” “Delighted,” said the tiny. “Mine is Gluckuk.”

The night-hob bowed without getting up. “My name is Vooshvazool.” “And mine,” the rock chewer crackled, “is Pyornkrachzark.”

All three looked at the will-o’-the-wisp, who was wriggling with embarrassment.

Will-o’-the-wisps find it most unpleasant to be looked full in the face. “Won’t you sit down, dear Blubb?” said the tiny.

“To tell the truth,” said the will-o’-the-wisp, “I’m in a terrible hurry. I only wanted to ask if by any chance you knew the way to the Ivory Tower.”

“Hoo,” said the night-hob. “Could you be going to see the Childlike Empress?”

“Exactly,” said the will-o’-the-wisp. “I have an important message for her.” “What does it say?” the rock chewer crackled.

“But you see,” said the will-o’-the-wisp, shifting its weight from foot to foot, “it’s a secret message.”

“All three of us—hoo—have the same mission as you,” replied Vooshvazool, the night-hob. “That makes us partners.”

“Maybe we even have the same message,” said Gluckuk, the tiny. “Sit down and tell us,” Pyornkrachzark crackled.

The will-o’-the-wisp sat down in the empty place.

“My home,” it began after a moment’s hesitation, “is a long way from here. I don’t know if any of those present has heard of it. It’s called Moldymoor.”

“Hoo!” cried the night-hob delightedly. “A lovely country!” The will-o’-the-wisp smiled faintly.

“Yes, isn’t it?”

“Is that all you have to say, Blubb?” Pyornkrachzark crackled. “What is the purpose of your trip?”

“Something has happened in Moldymoor,” said the will-o’-the-wisp haltingly, “something impossible to understand. Actually, it’s still happening. It’s hard to describe—the way it began was—well, in the east of our country there’s a lake— that is, there was a lake—Lake Foamingbroth we called it. Well, the way it began was like this. One day Lake Foamingbroth wasn’t there anymore—it was gone. See?”

“You mean it dried up?” Gluckuk inquired.

“No,” said the will-o’-the-wisp. “Then there’d be a dried-up lake. But there isn’t.

Where the lake used to be there’s nothing—absolutely nothing. Now do you see?”

“A hole?” the rock chewer grunted.

“No, not a hole,” said the will-o’-the-wisp despairingly. “A hole, after all, is something. This is nothing at all.”

The three other messengers exchanged glances. “What—hoo—does this nothing look like?” asked the night-hob.

“That’s just what’s so hard to describe,” said the will-o’-the-wisp unhappily. “It doesn’t look like anything. It’s—it’s like—oh, there’s no word for it.”

“Maybe,” the tiny suggested, “when you look at the place, it’s as if you were blind.”

The will-o’-the-wisp stared openmouthed.

“Exactly!” it cried. “But where—I mean how—I mean, have you had the same. ..?”

“Wait a minute,” the rock chewer crackled. “Was it only this one place?”

“At first, yes,” the will-o’-the-wisp explained. “That is, the place got bigger little by little. And then all of a sudden Foggle, the father of the frogs, who lived in Lake Foamingbroth with his family, was gone too. Some of the inhabitants started running away. But little by little the same thing happened to other parts of Moldymoor. It usually started with just a little chunk, no bigger than a partridge egg. But then these chunks got bigger and bigger. If somebody put his foot into one of them by mistake, the foot—or hand—or whatever else he put in—would be gone too. It didn’t hurt—it was just that a part of whoever it was would be missing. Some would even fall in on purpose if they got too close to the Nothing. It has an irresistible attraction—the bigger the place, the stronger the

pull. None of us could imagine what this terrible thing might be, what caused it, and what we could do about it. And seeing that it didn’t go away by itself but kept spreading, we finally decided to send a messenger to the Childlike Empress to ask her for advice and help. Well, I’m the messenger.”

The three others gazed silently into space.

After a while, the night-hob sighed: “Hoo! It’s the same where I come from.

And I’m traveling on the exact same errand—hoo hoo!”

The tiny turned to the will-o’-the-wisp. “Each one of us,” he chirped, “comes from a different province of Fantastica. We’ve met here entirely by chance. But each one of us is going to the Childlike Empress with the same message.”

“And the message,” grated the rock chewer, “is that all Fantastica is in danger.”

The will-o’-the-wisp cast a terrified look at each one in turn.

“If that’s the case,” it cried, jumping up, “we haven’t a moment to lose.”

“We were just going to start,” said the tiny. “We only stopped to rest because it’s so awfully dark here in Howling Forest. But now that you’ve joined us, Blubb, you can light the way.”

“Impossible,” said the will-o’-the-wisp. “Would you expect me to wait for someone who rides a snail? Sorry.”

“But it’s a racing snail,” said the tiny, somewhat miffed.

“Otherwise—hoo hoo—” the night-hob sighed, “we won’t tell you which way to go.”

“Who are you people talking to?” the rock chewer crackled.

And sure enough, the will-o’-the-wisp hadn’t even heard the other messengers’ last words, for it was already flitting through the forest in long leaps.

“Oh well,” said the tiny, pushing his top hat onto the back of his head, “maybe it wouldn’t have been such a good idea to follow a will-o’-the-wisp.”

“To tell the truth,” said the night-hob, “I prefer to travel on my own. Because I, for one, fly.”

With a quick “hoo hoo” he ordered his bat to make ready. And whish! Away he flew.

The rock chewer put out the campfire with the palm of his hand.

“I, too, prefer to go by myself,” he crackled in the darkness. “Then I don’t need to worry about squashing some wee creature.”

Rattling and grinding, he rode his stone bicycle straight into the woods, now and then thudding into a tree giant. Slowly the clatter receded in the distance.

Gluckuk, the tiny, was last to set out. He seized the silvery reins and said: “All right, we’ll see who gets there first. Geeyap, old-timer, geeyap.” And he clicked his tongue.

And then there was nothing to be heard but the storm wind howling in the treetops.

The clock in the belfry struck nine. Reluctantly Bastian’s thought turned back to reality. He was glad the Neverending Story had nothing to do with that.

He didn’t like books in which dull, cranky writers describe humdrum events in the very humdrum lives of humdrum people. Reality gave him enough of that kind of thing, why should he read about it? Besides, he couldn’t stand it when a writer tried to convince him of something. And these humdrum books, it seemed to him, were always trying to do just that.

Bastion liked books that were exciting or funny, or that made him dream. Books where made-up characters had marvelous adventures, books that made him imagine all sorts of things.

Because one thing he was good at, possibly the only thing, was imagining things so clearly that he almost saw and heard them. When he told himself stories, he sometimes forgot everything around him and awoke—as though from a dream—only when the story was finished. And this book was just like his own stories! In reading it, he had heard not only the creaking of the big trees and the howling of the wind in the treetops, but also the different voices of the four comical messengers. And he almost seemed to catch the smell of moss and forest earth.

Down in the classroom they were starting in on nature study. That consisted almost entirely in counting pistils and stamens. Bastian was glad to be up here in his hiding place, where he could read. This, he thought, was just the right book for him!

A week later Vooshvazool, the little night-hob, arrived at his destination. He was the first. Or rather, he thought he was first, because he was riding through the air.

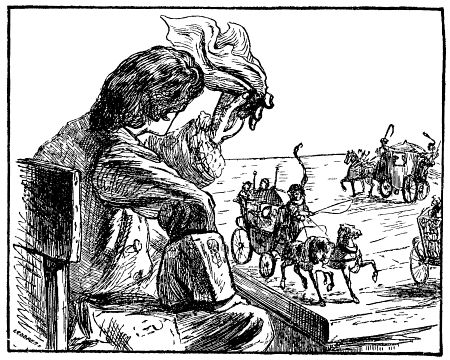

Just as the setting sun turned the clouds to liquid gold, he noticed that his bat was circling over the Labyrinth. That was the name of an enormous garden, extending from horizon to horizon and filled with the most bewitching scents and dreamlike colors.

Broad avenues and narrow paths twined their way among copses, lawns, and

beds of the rarest, strangest flowers in a design so artful and intricate that the whole plain resembled an enormous maze. Of course, it had been designed only for pleasure and amusement, with no intention of endangering anyone, much less of warding off an enemy. It would have been useless for such purposes, and the Childlike Empress required no such protection, because in all the unbounded reaches of Fantastica there was no one who would have thought of attacking her. For that there was a reason, as we shall soon see.

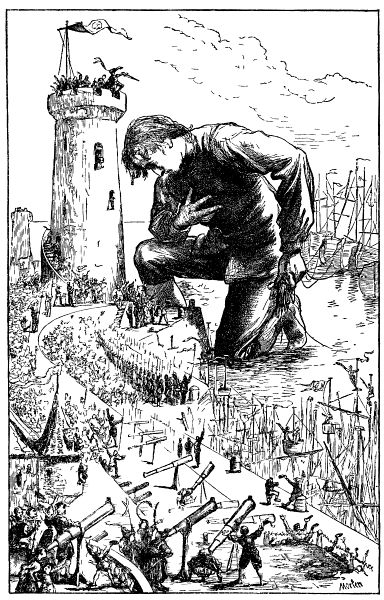

While gliding soundlessly over the flowery maze, the night-hob sighted all sorts of animals. In a small clearing between lilacs and laburnum, a group of young unicorns was playing in the evening sun, and once, glancing under a giant bluebell, he even thought he saw the famous phoenix in its nest, but he wasn’t quite certain, and such was his haste that he didn’t want to turn back to make sure. For at the center of the Labyrinth there now appeared, shimmering in fairy whiteness, the Ivory Tower, the heart of Fantastica and the residence of the Childlike Empress.

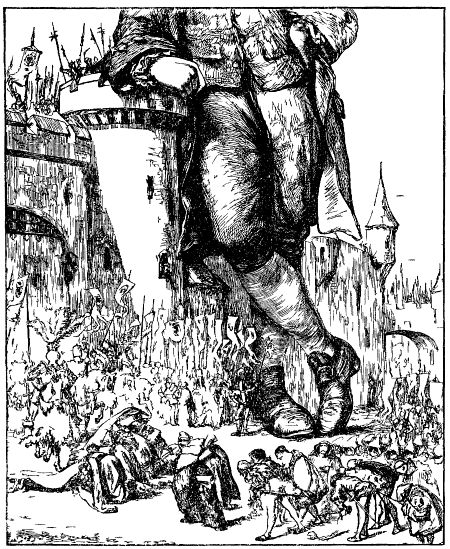

The word “tower” might give someone who has never seen it the wrong idea. It had nothing of the church or castle about it. The Ivory Tower was as big as a whole city.

From a distance it looked like a pointed mountain peak twisted like a snail shell. Its highest point was deep in the clouds. Only on coming closer could you notice that this great sugarloaf consisted of innumerable towers, turrets, domes, roofs, oriels, terraces, arches, stairways, and balustrades, all marvelously fitted together. The whole was made of the whitest Fantastican ivory, so delicately carved in every detail that it might have been taken for the latticework of the finest lace.

These buildings housed the Childlike Empress’s court, her chamberlains and maidservants, wise women and astrologers, magicians and jesters, messengers, cooks and acrobats, her tightrope walkers and storytellers, heralds, gardeners, watchmen, tailors, shoemakers and alchemists. And at the very summit of the great tower lived the Childlike Empress in a pavilion shaped like a magnolia blossom. On certain nights, when the full moon shone most gloriously in the starry sky, the ivory petals opened wide, and the Childlike Empress would be sitting in the middle of the glorious flower.

Riding on his bat, the little night-hob landed on one of the lower terraces, where the stables were located. Someone must have announced his arrival, for five imperial grooms were there waiting for him. They helped him out of his saddle, bowed to him, and held out the ceremonial welcome cup. As etiquette

demanded, Vooshvazool took only a sip and then returned the cup. Each of the grooms took a sip, then they bowed again and led the bat to the stables. All this was done in silence. On reaching its appointed place, the bat touched neither food nor drink, but immediately rolled up, hung itself head-down on a hook, and fell into a deep sleep. The little night-hob had demanded a bit too much of his mount. The grooms left it alone and crept away from the stable on tiptoes.

In this stable there were many other mounts: two elephants, one pink and one blue, a gigantic griffon with the forequarters of an eagle and the hindquarters of a lion, a winged horse, whose name was once known even outside of Fantastica but is now forgotten, several flying dogs, a few other bats, and several dragonflies and butterflies for especially small riders. In other stables there were still other mounts, which didn’t fly but ran, crawled, hopped, or swam. And each had a groom of its own to feed and take care of it.

Ordinarily one would have expected to hear quite a cacophony of different voices: roaring, screeching, piping, chirping, croaking, and chattering. But that day there was utter silence.

The little night-hob was still standing where the grooms had left him. Suddenly, without knowing why, he felt dejected and discouraged. He too was exhausted after the long trip. And not even the knowledge that he had arrived first could cheer him up.

Suddenly he heard a chirping voice. “Hello, hello! If it isn’t my good friend Vooshvazool! So glad you’ve finally made it!”

The night-hob looked around, and his moon eyes flared with amazement, for on a balustrade, leaning negligently against a flower pot, stood Gluckuk, the tiny, tipping his red top hat.

“Hoo hoo!” went the bewildered night-hob. And again: “Hoo hoo!” He just couldn’t think of anything better to say.

“The other two haven’t arrived yet. I’ve been here since yesterday morning.” “How—hoo hoo—how did you do it?”

“Simple,” said the tiny with a rather condescending smile. “Didn’t I tell you I had a racing snail?”

The night-hob scratched his tangled black head fur with his little pink hand. “I must go to the Childlike Empress at once,” he said mournfully.

The tiny gave him a pensive look.

“Hmm,” he said. “I put in for an appointment yesterday.”

“Put in for an appointment?” asked the night-hob. “Can’t we just go in and see her?”

“I’m afraid not,” chirped the tiny. “We’ll have a long wait. You can’t imagine how many messengers have turned up.”

“Hoo hoo,” the night-hob sighed. “How come?”

“You’d better take a look for yourself,” the tiny twittered. “Come with me, my dear Vooshvazool. Come with me!”

The two of them started out.

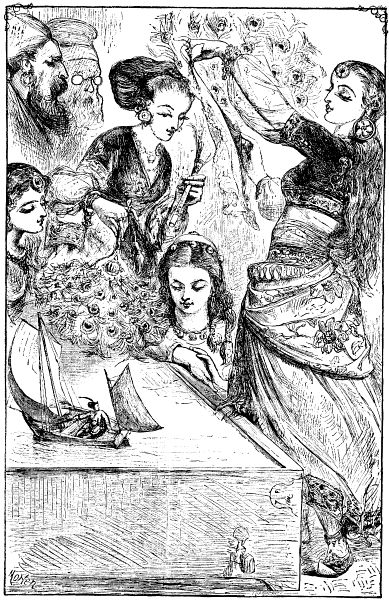

The High Street, which wound around the Ivory Tower in a narrowing spiral, was clogged with a dense crowd of the strangest creatures. Enormous beturbaned djinns, tiny kobolds, three-headed trolls, bearded dwarfs, glittering fairies, goat- legged fauns, nixies with wavy golden hair, sparkling snow sprites, and countless others were milling about, standing in groups, or sitting silently on the ground, discussing the situation or gazing glumly into the distance.

Vooshvazool stopped still when he saw them.

“Hoo hoo,” he said. “What’s going on? What are they all doing here?” “They’re all messengers,” Gluckuk explained. “Messengers from all over

Fantastica. All with the same message as ours. I’ve spoken with several of them. The same menace seems to have broken out everywhere.”

The night-hob gave vent to a long wheezing sigh.

“Do they know,” he asked, “what it is and where it comes from?” “I’m afraid not. Nobody knows.”

“What about the Childlike Empress?”

“The Childlike Empress,” said the tiny in an undertone, “is ill, very ill. Maybe that’s the cause of this mysterious calamity that’s threatening all Fantastica. But so far none of the many doctors who’ve been conferring in the Magnolia Pavilion has discovered the nature of her illness or found a cure for it.”

“That,” said the night-hob breathlessly, “is—hoo hoo—terrible.” “So it is,” said the tiny.

In view of the circumstances, Vooshvazool decided not to put in for an appointment.

Two days later Blubb, the will-o’-the-wisp, arrived. Of course, he had hopped in the wrong direction and made an enormous detour.

And finally—three days after that—Pyornkrachzark, the rock chewer, appeared.

He came plodding along on foot, for in a sudden frenzy of hunger he had eaten his stone bicycle.

During the long waiting period, the four so unalike messengers became good friends. From then on they stayed together.

But that’s another story and shall be told another time.

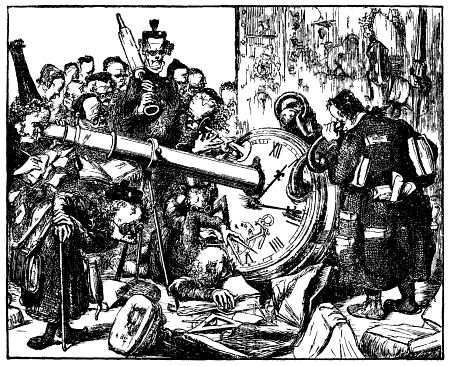

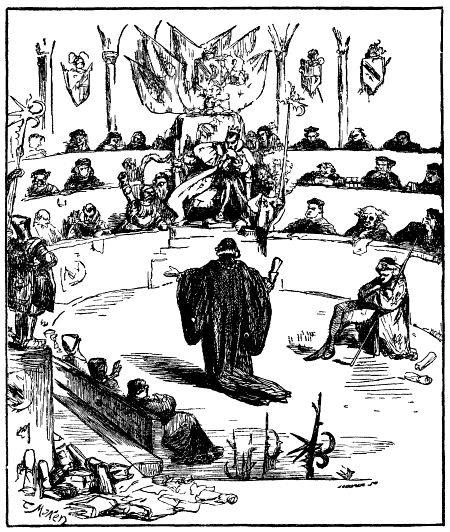

ecause of their special importance, deliberations concerning the welfare of all Fantastica were held in the great throne room of the palace, which was situated only a few floors below the Magnolia Pavilion.

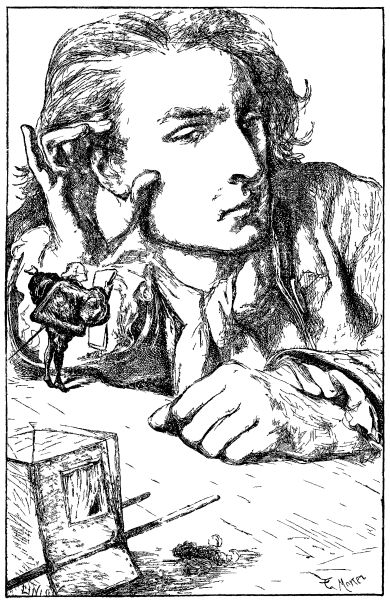

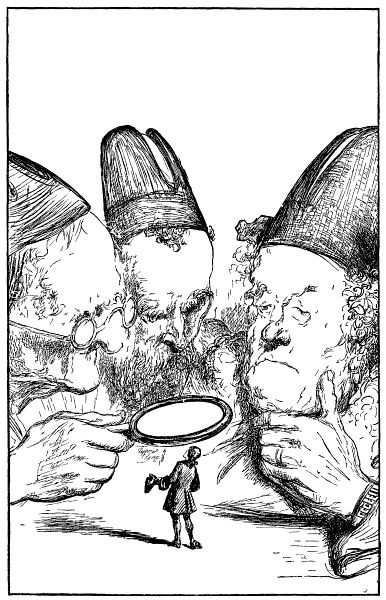

The large circular room was filled with muffled voices. The four hundred and ninety-nine best doctors in Fantastica had assembled there and were whispering or mumbling with one another in groups of varying sizes. Each one had examined the Childlike Empress—some more recently than others—and each had tried to help her with his skill. But none had succeeded, none knew the nature or cause of her illness, and none could think of a cure for it. Just then the five hundredth doctor, the most famous in all Fantastica, whose knowledge was said to embrace every existing medicinal herb, every magic philtre and secret of nature, was examining the patient. He had been with her for several hours, and all his assembled colleagues were eagerly awaiting the result of his examination. Of course, this assembly was nothing like a human medical congress. To be

sure, a good many of the inhabitants of Fantastica were more or less human in appearance, but at least as many resembled animals or were even farther from the human. The doctors inside the hall were just as varied as the crowd of messengers milling about outside.

There were dwarf doctors with white beards and humps, there were fairy doctoresses in shimmering silvery-blue robes and with glittering stars in their hair, there were water sprites with big round bellies and webbed hands and feet (sitz baths had been installed for them) . There were white snakes, who had coiled up on the long table at the center of the room; there were witches, vampires, and ghosts, none of whom are generally reputed to be especially benevolent or conducive to good health.

If you are to understand why these last were present, there is one thing you have to know:

The Childlike Empress—as her title indicates—was looked upon as the ruler over all the innumerable provinces of the Fantastican Empire, but in reality she was far more than a ruler; she was something entirely different.

She didn’t rule, she had never used force or made use of her power. She never issued commands and she never judged anyone. She never interfered with anyone and never had to defend herself against any assailant; for no one would have thought of rebelling against her or of harming her in any way. In her eyes all her subjects were equal.

She was simply there in a special way. She was the center of all life in Fantastica.

And every creature, whether good or bad, beautiful or ugly, merry or solemn, foolish or wise—all owed their existence to her existence. Without her, nothing could have lived, any more than a human body can live if it has lost its heart.

All knew this to be so, though no one fully understood her secret. Thus she was respected by all the creatures of the Empire, and her health was of equal concern to them all. For her death would have meant the end of them all, the end of the boundless Fantastican realm.

Bastian’s thoughts wandered.

Suddenly he remembered the long corridor in the hospital where his mother had been operated on. He and his father had sat waiting for hours outside the operating room. Doctors and nurses hurried this way and that. When his father asked about his wife, the answer was always evasive. No one really seemed to know how she was doing.

Finally a bald-headed man in a white smock had come out to them. He looked tired and sad. Much as he regretted it, he said, his efforts had been in vain. He had pressed their hands and mumbled something about “heartfelt sympathy.”

After that, everything had changed between Bastion and his father. Not outwardly. Bastion had everything he could have wished for. He had a three- speed bicycle, an electric train, plenty of vitamin pills, fifty-three books, a golden hamster, an aquarium with tropical fish in it, a small camera, six pocketknives, and so forth and so on. But none of all this really meant anything to him.

Bastian remembered that his father had often played with him in the past. He had even told him stories. No longer. He couldn’t talk to his father anymore. There was an invisible wall around his father, and no one could get through to him. He never found fault and he never praised. Even when Bastian was put back in school, his father hadn’t said anything. He had only looked at him in his sad, absent way, and Bastian felt that as far as his father was concerned he wasn’t there at all. That was how his father usually made him feel. When they sat in front of the television screen in the evening, Bastian saw that his father wasn’t even looking at it, that his thoughts were far away. Or when they both sat there with books, Bastian saw that his father wasn’t reading at all. He’d been looking at the same page for hours and had forgotten to turn it.

Bastian knew his father was sad. He himself had cried for many nights— sometimes he had been so shaken by sobs that he had to vomit—but little by little it had passed. And after all he was still there. Why didn’t his father ever speak to him, not about his mother, not about important things, but just for the feel of talking together?

“If only we knew,” said a tall, thin fire sprite, with a beard of red flames, “if only we knew what her illness is. There’s no fever, no swelling, no rash, no inflammation. She just seems to be fading away—no one knows why.”

As he spoke, little clouds of smoke came out of his mouth and formed figures. This time they were question marks.

A bedraggled old raven, who looked like a potato with feathers stuck onto it every which way, answered in a croaking voice (he was a head cold and sore throat specialist):

“She doesn’t cough, she hasn’t got a cold. Medically speaking, it’s no disease at all.” He adjusted the big spectacles on his beak and a cast a challenging look around.

“One thing seems obvious,” buzzed a scarab (a beetle, sometimes known as a pill roller): “There is some mysterious connection between her illness and the terrible happenings these messengers from all Fantastica have been reporting.”

“Oh yes!” scoffed an ink goblin. “You see mysterious connections everywhere.”

“My dear colleague!” pleaded a hollow-cheeked ghost in a long white gown. “Let’s not get personal. Such remarks are quite irrelevant. And please—lower

your voices.”

Conversations of this kind were going on in every part of the throne room. It may seem strange that creatures of so many different kinds were able to communicate with one another. But nearly all the inhabitants of Fantastica, even the animals, knew at least two languages: their own, which they spoke only with members of their own species and which no outsider understood, and the universal language known as High Fantastican. All Fantasticans used it, though some in a rather peculiar way.

Suddenly all fell silent, for the great double door had opened. In stepped Cairon, the far-famed master of the healer’s art.

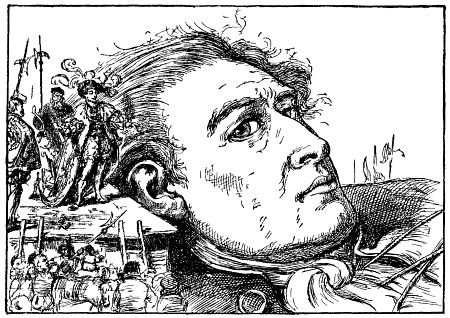

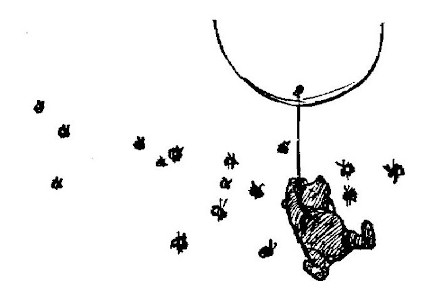

He was what in older times had been called a centaur. He had the body of a man from the waist up, and that of a horse from the waist down. And Cairon was furthermore a black centaur. He hailed from a remote region far to the south, and his human half was the color of ebony. Only his curly hair and beard were white, while the horselike half of him was striped like a zebra. He was wearing a strange hat plaited of reeds. A large golden amulet hung from a chain around his neck, and on this amulet one could make out two snakes, one light and one dark, which were biting each other’s tail and so forming an oval.

Everyone in Fantastica knew what the medallion meant. It was the badge of one acting on orders from the Childlike Empress, acting in her name as though she herself were present.

It was said to give the bearer mysterious powers, though no one knew exactly what these powers were. Everyone knew its name: AURYN.

But many, who feared to pronounce the name, called it the “Gem” or the “Glory”.

In other words, the book bore the mark of the Childlike Empress!

A whispering passed through the throne room, and some of the doctors were heard to cry out. The Gem had not been entrusted to anyone for a long, long

time.

Cairon stamped his hooves two or three times. When the disorder subsided, he said in a deep voice: “Friends, don’t be too upset. I shall only be wearing AURYN for a short time. I am merely a go-between. Soon I shall pass the Gem on to one worthier.”

A breathless silence filled the room.

“I won’t try to misrepresent our defeat with high-sounding words. The Childlike Empress’s illness has baffled us all. The one thing we know is that the destruction of Fantastica began at the same time as this illness. We can’t even be sure that medical science can save her. But it is possible—and I hope none of you will be offended at what I am going to say—it is possible that we, we who are gathered here, do not possess all knowledge, all wisdom. Indeed it is my last and only hope that somewhere in this unbounded realm there is a being wiser than we are, who can give us help and advice. Of course, this is no more than a possibility. But one thing is certain: The search for this savior calls for a pathfinder, someone who is capable of finding paths in the pathless wilderness and who will shrink from no danger or hardship. In other words: a hero. And the Childlike Empress has given me the name of this hero, to whom she entrusts her salvation and ours. His name is Atreyu, and he lives in the Grassy Ocean beyond the Silver Mountains. I shall transmit AURYN to him and send him on the Great Quest. Now you know all there is to know.”

With that, the old centaur thumped out of the room.

Those who remained behind exchanged looks of bewilderment. “What was this hero’s name?” one of them asked.

“Atreyu or something of the kind,” said another.

“Never heard of him,” said the third. And all four hundred and ninety-nine doctors shook their heads in dismay.

The clock in the belfry struck ten. Bastian was amazed at how quickly the time had passed. In class, every hour seemed to drag on for an eternity. Down below, they would be having history with Mr. Drone, a gangling, ordinarily ill- tempered man, who delighted in holding Bastian up to ridicule because he couldn’t remember the dates when certain battles had been fought or when someone or other had reigned.

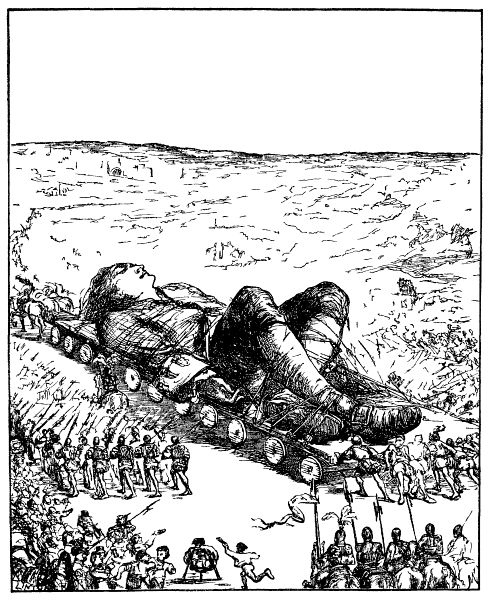

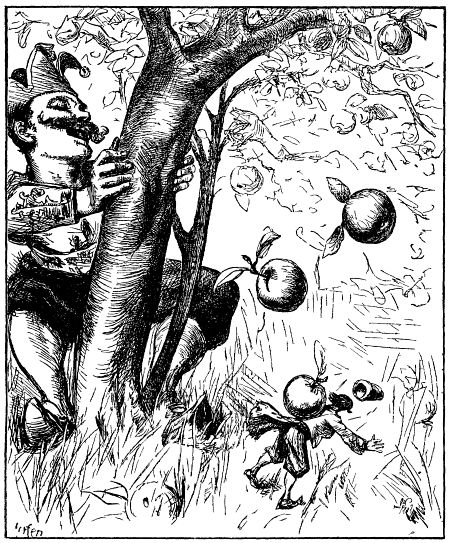

The Grassy Ocean behind the Silver Mountains was many days’ journey from the Ivory Tower. It was actually a prairie, as long and wide and flat as an ocean.

Its whole expanse was covered with tall, juicy grass, and when the wind blew, great waves passed over it with a sound like troubled water.

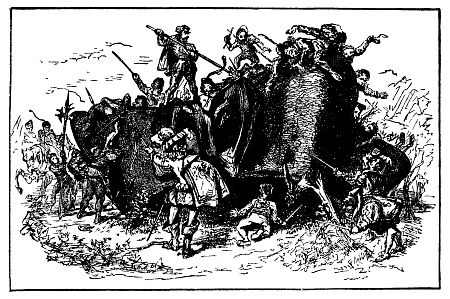

The people who lived there were known as “Grass People” or “Greenskins”. They had blue-black hair, which the men as well as the women wore long and often in pigtails, and their skin was olive green. They led a hard, frugal life, and their children, girls as well as boys, were brought up to be brave, proud, and generous. They learned to bear heat, cold, and great hardship and were tested for courage at an early age. This was necessary because the Greenskins were a nation of hunters. They obtained everything they needed either from the hard, fibrous prairie grass or from the purple buffaloes, great herds of which roamed the Grassy Ocean.

These purple buffaloes were about twice the size of common bulls or cows; they had long, purplish-red hair with a silky sheen and enormous horns with tips as hard and sharp as daggers. They were peaceful as a rule, but when they scented danger or thought they were being attacked, they could be as terrible as a natural cataclysm. Only a Greenskin would have dared to hunt these beasts, and moreover they used no other weapons than bows and arrows. The Greenskins were believers in chivalrous combat, and often it was not the hunted but the hunter who lost his life. The Greenskins loved and honored the purple buffaloes and held that only those willing to be killed by them had the right to kill them.

News of the Childlike Empress’s illness and the danger threatening all Fantastica had not yet reached the Grassy Ocean. It was a long, long time since any traveler had visited the tent colonies of the Greenskins. The grass was juicier than ever, the days were bright, and the nights full of stars. All seemed to be well.

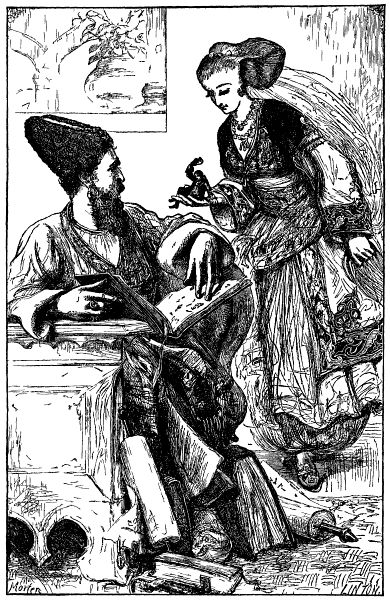

But one day a white-haired black centaur appeared. His hide was dripping with sweat, he seemed totally exhausted, and his bearded face was haggard. On his head he wore a strange hat plaited of reeds, and around his neck a chain with a large golden amulet hanging from it. It was Cairon.

He stood in the open space at the center of the successive rings of tents. It was there that the elders held their councils and that the people danced and sang old songs on feast days. He waited for the Greenskins to assemble, but it was only very old men and women and small children wide-eyed with curiosity who crowded around him. He stamped his hooves impatiently.

“Where are the hunters and huntresses?” he panted, removing his hat and wiping his forehead.

A white-haired woman with a baby in her arms replied: “They are still

hunting.

They won’t be back for three or four days.” “Is Atreyu with them?” the centaur asked.

“Yes, stranger, but how can it be that you know him?” “I don’t know him. Go and get him.”

“Stranger,” said an old man on crutches, “he will come unwillingly, because this is his hunt. It starts at sunset. Do you know what that means?”

Cairon shook his mane and stamped his hooves.

“I don’t know, and it doesn’t matter. He has something more important to do now. You know this sign I am wearing. Go and get him.”

“We see the Gem,” said a little girl. “And we know you have come from the Childlike Empress. But who are you?”

“My name is Cairon,” the centaur growled. “Cairon the physician, if that means anything to you.”

A bent old woman pushed forward and cried out: “Yes, it’s true. I recognize him. I saw him once when I was young. He is the greatest and most famous doctor in all Fantastica.”

The centaur nodded. “Thank you, my good woman,” he said. “And now perhaps one of you will at last be kind enough to bring this Atreyu here. It’s urgent. The life of the Childlike Empress is at stake.”

“I’ll go,” cried a little girl of five or six.

She ran away and a few seconds later she could be seen between the tents galloping away on a saddleless horse.

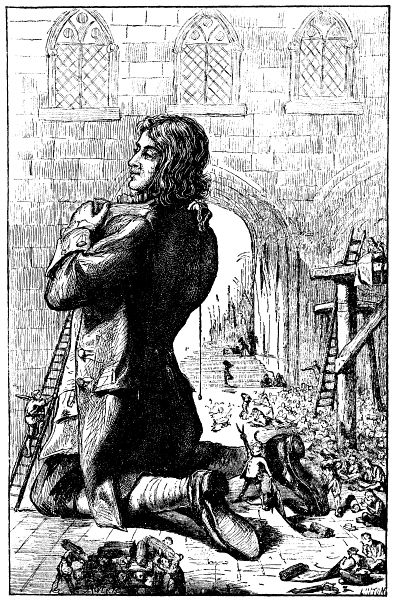

“At last!” Cairon grumbled. Then he fell into a dead faint. When he revived, he didn’t know where he was, for all was dark around him. It came to him only little by little that he was in a large tent, lying on a bed of soft furs. It seemed to be night, for through a cleft in the door curtain he saw flickering firelight.

“Holy horseshoes!” he muttered, and tried to sit up. “How long have I been lying here?”

A head looked in through the door opening and pulled back again. Someone said:

“Yes, he seems to be awake.”

Then the curtain was drawn aside and a boy of about ten stepped in. His long trousers and shoes were of soft buffalo leather. His body was bare from the waist up, but a long purple-red cloak, evidently woven from buffalo hair, hung from his shoulders. His long blue-black hair was gathered together and held back by leather thongs. A few simple white designs were painted on the olive-green skin

of his cheeks and forehead. His dark eyes flashed angrily at the intruder; otherwise his features betrayed no emotion of any kind.

“What do you want of me, stranger?” he asked. “Why have you come to my tent? And why have you robbed me of my hunt? If I had killed the big buffalo today—and my arrow was already fitted to my bowstring—I’d have been a hunter tomorrow. Now I’ll have to wait a whole year. Why?”

The old centaur stared at him in consternation. “Am I to take it,” he asked, “that you are Atreyu?”

“That’s right, stranger.”

“Isn’t there someone else of the same name? A grown man, an experienced hunter?”

“No. I and no one else am Atreyu.”

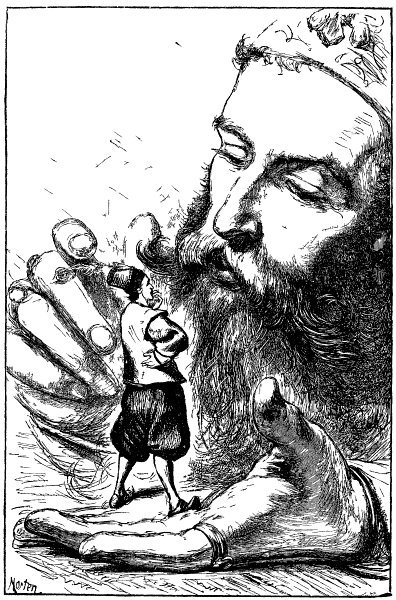

Sinking back on his bed of furs, old Cairon gasped: “A child! A little boy!

Really, the decisions of the Childlike Empress are hard to fathom.” Atreyu waited in impassive silence.

“Forgive me, Atreyu,” said Cairon, controlling his agitation with the greatest difficulty. “I didn’t mean to hurt your feelings, but the surprise has been just too great. Frankly, I’m horrified. I don’t know what to think. I can’t help wondering: Did the Childlike Empress really know what she was doing when she chose a youngster like you? It’s sheer madness! And if she did it intentionally, then . . . then . . .”

With a violent shake of his head, he blurted out: “No! No! If I had known whom she was sending me to, I’d have refused to entrust you with the mission. I’d have refused!”

“What mission?” Atreyu asked.

“It’s monstrous!” cried Cairon indignantly. “It’s doubtful whether even the greatest, most experienced of heroes could carry out this mission . . . and you! . . . She’s sending you into the unfathomable to look for the unknown . . . No one can help you, no one can advise you, no one can foresee what will befall you. And yet you must decide at once, immediately, whether or not you accept the mission. There’s not a moment to be lost. For ten days and nights I have galloped almost without rest to reach you. But now—I almost wish I hadn’t got here. I’m very old, I’m at the end of my strength. Give me a drink of water, please.”

Atreyu brought a pitcher of fresh spring water. The centaur drank deeply, then he wiped his beard and said somewhat more calmly: “Thank you. That was good. I feel better already. Listen to me, Atreyu. You don’t have to accept this

mission. The Childlike Empress leaves it entirely up to you. She never gives orders. I’ll tell her how it is and she’ll find someone else. She can’t have known you were a little boy. She must have got you mixed up with someone else. That’s the only possible explanation.”

“What is this mission?” Atreyu asked.

“To find a cure for the Childlike Empress,” the centaur answered, “and save Fantastica.”

“Is she sick?” Atreyu asked in amazement.

Cairon told him how it was with the Childlike Empress and what the messengers had reported from all parts of Fantastica. Atreyu asked many questions and the centaur answered them to the best of his ability. They talked far into the night. And the more Atreyu learned of the menace facing Fantastica, the more his face, which at first had been so impassive, expressed unveiled horror.

“To think,” he murmured finally with pale lips, “that I knew nothing about it!”

Cairon cast a grave, anxious look at the boy from under his bushy white eyebrows.

“Now you know the lie of the land,” he said. “And now perhaps you understand why I was so upset when I first laid eyes on you. Still, it was you the Childlike Empress named. ‘Go and find Atreyu,’ she said to me. ‘I put all my trust in him,’ she said. ‘Ask him if he’s willing to attempt the Great Quest for me and for Fantastica.’ I don’t know why she chose you. Maybe only a little boy like you can do whatever has to be done. I don’t know, and I can’t advise you.”

Atreyu sat there with bowed head, and made no reply. He realized that this was a far greater task than his hunt. It was doubtful whether the greatest hunter and pathfinder could succeed; how then could he hope . . .?

“Well?” the centaur asked. “Will you?” Atreyu raised his head and looked at him. “I will,” he said firmly.

Cairon nodded gravely. Then he took the chain with the golden amulet from his neck and put it around Atreyu’s.

“AURYN gives you great power,” he said solemnly, “but you must not make use of it. For the Childlike Empress herself never makes use of her power. AURYN will protect you and guide you, but whatever comes your way you must never interfere, because from this moment on your own opinion ceases to count. For that same reason you must go unarmed. You must let what happens happen. Everything must be equal in your eyes, good and evil, beautiful and ugly, foolish

and wise, just as it is in the eyes of the Childlike Empress. You may only search and inquire, never judge. Always remember that, Atreyu!”

“AURYN!” Atreyu repeated with awe. “I will be worthy of the Glory. When should I start?”

“Immediately,” said Cairon. “No one knows how long your Great Quest will be. Every hour may count, even now. Say goodbye to your parents and your brothers and sisters.”

“I have none,” said Atreyu. “My parents were both killed by a buffalo, soon after I was born.”

“Who brought you up?”

“All the men and women together. That’s why they called me Atreyu, which in our language means ‘Son of All’!”

No one knew better than Bastion what that meant. Even though his father was still alive and Atreyu had neither father nor mother. To make up for it, Atreyu had been brought up by all the men and women together and was the “son of all”, while Bastian had no one—and was really “nobody’s son”. All the same, Bastian was glad to have this much in common with Atreyu, because otherwise he resembled him hardly at all, neither physically nor in courage and determination. Yet Bastian, too, was engaged in a Great Quest and didn’t know where it would lead him or how it would end.

“In that case,” said the old centaur, “you’d better go without saying goodbye.

I’ll stay here and explain.”

Atreyu’s face became leaner and harder than ever. “Where should I begin?” he asked.

“Everywhere and nowhere,” said Cairon. “From now on you will be on your own, with no one to advise you. And that’s how it will be until the end of the Great Quest—however it may end.”

Atreyu nodded. “Farewell, Cairon.”

“Farewell, Atreyu. And—much luck!”

The boy turned away and was leaving the tent when the centaur called him back.

As they stood face to face, the old centaur put both hands on Atreyu’s shoulders, looked him in the eye with a respectful smile, and said slowly: “I think I’m beginning to see why the Childlike Empress chose you, Atreyu.”

The boy lowered his head just a while. Then he went out quickly.

His horse, Artax, was standing outside the tent. He was small and spotted like a wild horse. His legs were short and stocky, but he was the fastest, most tireless runner far and wide. He was still saddled as Atreyu had ridden him back from the hunt.

“Artax,” Atreyu whispered, patting his neck. “We’re going away, far, far away. No one knows if we shall ever come back!”

The horse nodded his head and gave a brief snort. “Yes, master,” he said. “But what about your hunt?”

“We’re going on a much greater hunt,” said Atreyu, swinging himself into the saddle.

“Wait, master,” said the horse. “You’ve forgotten your weapons. Are you going without your bow and arrow?”

“Yes, Artax,” said Atreyu. “I have to go unarmed because I am bearing the Gem.”

“Humph!” snorted the horse. “And where are we going?”

“Wherever you like, Artax,” said Atreyu. “From this moment on we shall be on the Great Quest.”

With that they galloped away and were swallowed up by the darkness.

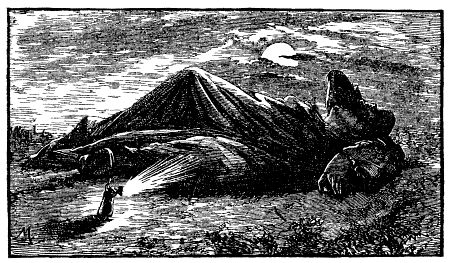

At the same time, in a different part of Fantastica, something happened which went completely unnoticed. Neither Atreyu nor Artax had the slightest inkling of it.

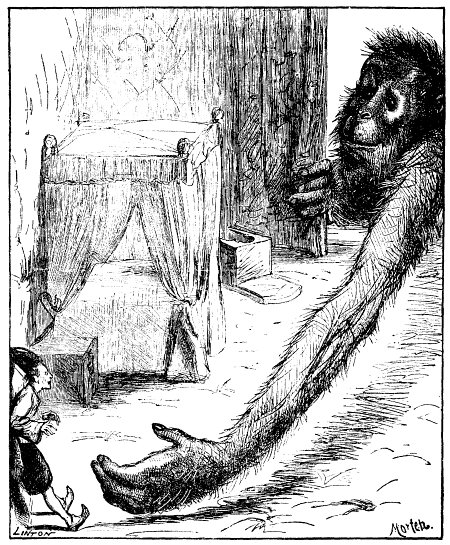

On a remote night-black heath the darkness condensed into a great shadowy form.

It became so dense that even in that moonless, starless night it came to look like a big black body. Its outlines were still unclear, but it stood on four legs and green fire glowed in the eyes of its huge shaggy head. It lifted up its great snout and stood for a long while, sniffing the air. Then suddenly it seemed to find the scent it was looking for, and a deep, triumphant growl issued from its throat.

And off it ran through the starless night, in long, soundless leaps.

The clock in the belfry struck eleven. From the downstairs corridors arose the shouts of children running out to the playground.

Bastian was still squatting cross-legged on the mats. His legs had fallen asleep. He wasn’t an Indian after all. He stood up, took his sandwich and an apple out of his satchel, and paced the floor. He had pins and needles in his feet, which took some time to wake up.

Then he climbed onto the horse and straddled it. He imagined he was Atreyu galloping through the night on Artax’s back. He leaned forward and rested his head on his horse’s neck.

“Gee!” he cried. “Run, Artax! Gee! Gee!”

Then he became frightened. It had been foolish of him to shout so loud. What if someone had heard him? He waited awhile and listened. But all he heard was the intermingled shouts from the yard.

Feeling rather foolish, he climbed down off the horse. Really, he was behaving like a small child!

He unwrapped his sandwich and shined the apple on his trousers. But just as he was biting into it, he stopped himself.

“No,” he said to himself aloud. “I must carefully apportion my provisions.

Who knows how long they will have to last me.”

With a heavy heart he rewrapped his sandwich and returned it to his satchel along with the apple. Then with a sigh he settled down on the mats and reached for the book.

airon, the old black centaur, sank back on his bed of furs as Artax’s hoofbeats were dying away. After so much exertion he was at the end of his strength. The women who found him next day in Atreyu’s tent feared for his life. And when the hunters came home a few days later, he was hardly any better, but he managed nevertheless to tell them why Atreyu had ridden away and would not be back soon. As they were all fond of the boy, their concern for him made them grave. Still, they were proud that the Childlike Empress had chosen him for the Great Quest—though none claimed to understand her choice.

Old Cairon never went back to the Ivory Tower. But he didn’t die and he didn’t stay with the Greenskins in the Grassy Ocean. His destiny was to lead him over very different and unexpected pathways. But that is another story and shall be told another time.

That same night Atreyu rode to the foot of the Silver Mountains. It was almost morning when he finally stopped to rest. Artax grazed a while and drank water

from a small mountain stream. Atreyu wrapped himself in his red cloak and slept a few hours.

But when the sun rose, they were already on their way.

On the first day they crossed the Silver Mountains, where every road and trail was known to them, and they made quick progress. When he felt hungry, the boy ate a chunk of dried buffalo meat and two little grass-seed cakes that he had been carrying in his saddlebag—originally they had been intended for his hunt.

“Exactly,” said Bastian. “A man has to eat now and then.”

He took his sandwich out of his satchel, unwrapped it, broke it carefully in two pieces, wrapped one of them up again and put it away. Then he ate the other. Recess was over. Bastian wondered what his class would be doing next. Oh yes, geography, with Mrs. Flint. You had to reel off rivers and their tributaries, cities, population figures, natural resources, and industries. Bastian shrugged his

shoulders and went on reading.

By sunset the Silver Mountains lay behind them, and again they stopped to rest.

That night Atreyu dreamed of purple buffaloes. He saw them in the distance, roaming over the Grassy Ocean, and he tried to get near them on his horse. In vain. He galloped, he spurred his horse, but they were always the same distance away.

The second day they passed through the Singing Tree Country. Each tree had a different shape, different leaves, different bark, but all of them in growing—and this was what gave the country its name—made soft music that sounded from far and near and joined in a mighty harmony that hadn’t its like for beauty in all Fantastica. Riding through this country wasn’t entirely devoid of danger, for many a traveler had stopped still as though spellbound and forgotten everything else. Atreyu felt the power of these marvelous sounds, but didn’t let himself be tempted to stop.

The following night he dreamed again of purple buffaloes. This time he was on foot, and a great herd of them was passing. But they were beyond the range of his bow, and when he tried to come closer, his feet clung to the ground and he couldn’t move them.

His frantic efforts to tear them loose woke him up. He started out at once, though the sun had not yet risen.

The third day, he saw the Glass Tower of Eribo, where the inhabitants of the

region caught and stored starlight. Out of the starlight they made wonderfully decorative objects, the purpose of which, however, was known to no one in all Fantastica but their makers.

He met some of these folk; little creatures they were, who seemed to have been blown from glass. They were extremely friendly and provided him with food and drink, but when he asked them who might know something about the Childlike Empress’s illness, they sank into a gloomy, perplexed silence.

The next night Atreyu dreamed again that the herd of purple buffaloes was passing. One of the beasts, a particularly large, imposing bull, broke away from his fellows and slowly, with no sign of either fear or anger, approached Atreyu. Like all true hunters, Atreyu knew every creature’s vulnerable spot, where an arrow wound would be fatal. The purple buffalo put himself in such a position as to offer a perfect target. Atreyu fitted an arrow to his bow and pulled with all his might. But he couldn’t shoot. His fingers seemed to have grown into the bowstring, and he couldn’t release it.

Each of the following nights he dreamed something of the sort. He got closer and closer to the same purple buffalo—he recognized him by a white spot on his forehead—but for some reason he was never able to shoot the deadly arrow.

During the days he rode farther and farther, without knowing where he was going or finding anyone to advise him. The golden amulet he wore was respected by all who met him, but none had an answer to his question.

One day he saw from afar the flaming streets of Salamander, the city whose inhabitants’ bodies are of fire, but he preferred to keep away from it. He crossed the broad plateau of the Sassafranians, who are born old and die when they become babies. He came to the jungle temple of Muwamath, where a great moonstone pillar hovers in midair, and he spoke to the monks who lived there. And again no one could tell him anything.

He had been traveling aimlessly for almost a week, when on the seventh day and the following night two very different encounters changed his situation and state of mind.

Cairon’s story of the terrible happenings in all parts of Fantastica had made an impression on him, but thus far the disaster was something he had only heard about. On the seventh day he was to see it with his own eyes.

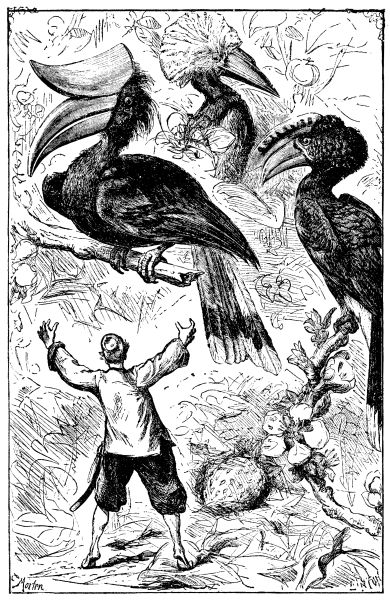

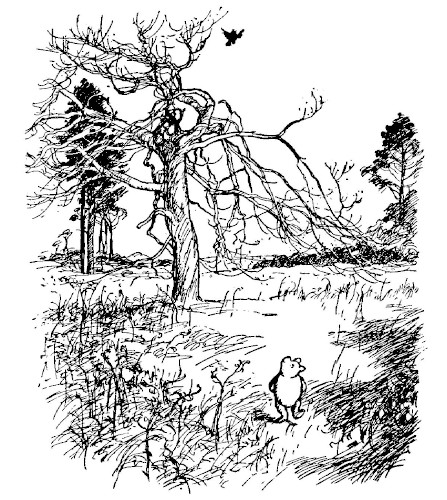

Toward noon, he was riding through a dense dark forest of enormous gnarled trees. This was the same Howling Forest where the four messengers had met some time before. That region, as Atreyu knew, was the home of bark trolls. These, as he had been told, were giants and giantesses, who themselves looked

like gnarled tree trunks. As long as they stood motionless, as they usually did, you could easily mistake them for trees and ride on unsuspecting. Only when they moved could you see that they had branchlike arms and crooked, rootlike legs. Though exceedingly powerful, they were not dangerous—at most they liked to play tricks on travelers who had lost their way.

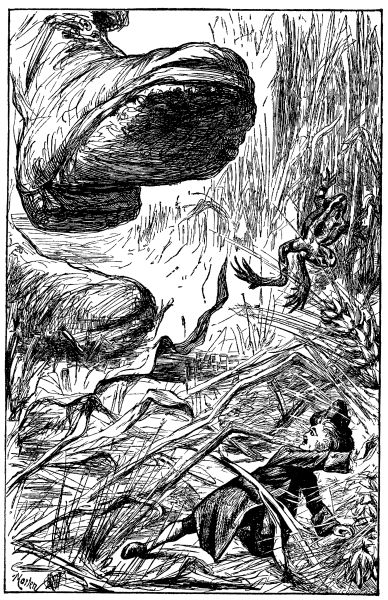

Atreyu had just discovered a woodland meadow with a brook twining through it, and had dismounted to let Artax drink and graze. Suddenly he heard a loud crackling and thudding in the woods behind him.